Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

The many agencies that responded to the Sept. 29 BioLab chemical fire in Conyers, Georgia, communicated poorly with the public — and each other — and the EPA failed to lead, GNR Health Department leaders said Friday.

It took three days for a joint information center to be established, making it hard to get accurate, timely messages to the media and the public, said Mark Reiswig, director of emergency preparedness for GNR Health, which covers Gwinnett, Newton and Rockdale counties.

“I started asking for that on Sunday,” the day of the fire, he said Friday at Rockdale County’s Board of Health meeting. “Between the groups here, it seemed to be a very challenging lift, and it was frustrating to the public, because the public was not getting the information you want, the public health messaging and press conferences.”

The Environmental Protection Agency’s failure to assume the lead role in the response created confusion, Reiswig said.

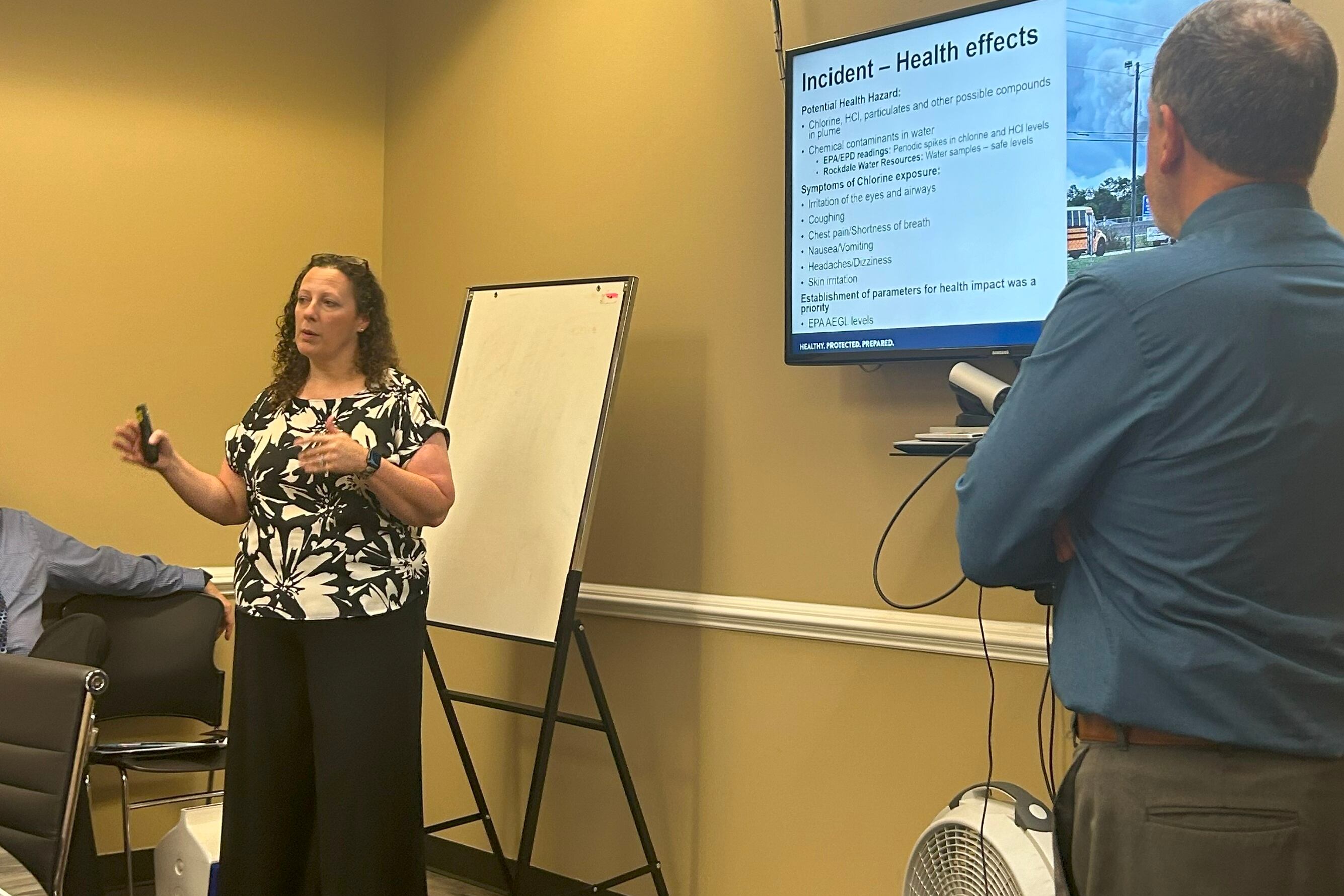

Rockdale health department’s nurses sprung into action to staff the shelters for evacuees. And interim District Health Director Dr. Lynn Paxton explained possible health effects of the fire during press conferences that helped reassure the public, Alana Sulka, chief clinical officer for GNR Health, said at the meeting.

The fire at the BioLab plant spewed multicolored smoke over Conyers, a small town about 30 miles east of Atlanta, forcing thousands to evacuate, shuttering schools and businesses, and causing many residents to seek medical attention for symptoms including cough, burning eyes and throats, or shortness of breath.

Smoke from the fire drifted over parts of metro Atlanta and lingered in Conyers for nearly three weeks.

The EPA created a website that provided updated air-quality data twice a day. Sulka said she asked the agency to translate its findings into common-sense terms but that never happened.

“They speak geek. They don’t speak public,” Reiswig said of the EPA.

“My observation was that everybody was scared to be responsible for sharing information,” Reiswig told Healthbeat after the meeting. “It’s just foolish to say, ‘Well, let’s just not say anything’ because then you’re saying, ‘Somebody else handle the narrative’,” which leads to rumors and false information.

The EPA did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Reiswig told the board his team considered whether local nursing homes and the Piedmont Rockdale Hospital should be evacuated.

But the fire started on the same day that Children’s Hospital of Atlanta had engaged 65 ambulance teams to transport 200 pediatric patients from the old Egleston facility in Decatur to the new Arthur M. Blank Hospital in Brookhaven as part of a long-planned hospital move.

“Oh my gosh, where are we going to get people to do this?” Reiswig recalled thinking.

Ultimately, the team decided evacuating Rockdale County facilities was not necessary. Instead, the facilities turned off their HVAC systems, Reiswig said.

At Friday’s meeting, Sulka provided an update on the Georgia Department of Public Health’s “syndromic surveillance” of the health effects of the fire.

Syndromic surveillance captures what’s happening in area emergency rooms and other clinics based on keywords in medical records. It doesn’t capture every single case or provide a deep look at what the outcome of each case is but rather provides a snapshot of health trends at a given time, state public health department spokeswoman Nancy Nydam said.

The state found 1,038 total visits to hospitals and urgent care clinics between Sept. 29, when the fire started, and Oct. 30. Most of the visits took place in the week after the fire.

About half came from Rockdale residents, 20% from Newton, and 10% from DeKalb.

Most of the visits — 80%— captured in the surveillance came from Black patients. White patients made up 10% of the patients.

Top symptoms included ear, nose, and throat irritation, cough, and chest pain or shortness of breath. Other symptoms included nausea and vomiting, skin and eye irritation, and headache or dizziness.

The presentation indicated an additional survey was developed and sent to private medical providers, but the agency received no responses.

Rockdale County Commissioner Doreen Williams, who sits on the board of public health, said residents are concerned about the long-term health effects of exposure to the smoke. “A year from now, 10 years from now, are there going to be repercussions?”

The state public health department “is not aware of any studies being conducted or longitudinal tracking systems to monitor individuals exposed to the smoke from the fire,” Nydam said, adding that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or a university might undertake such an effort.

Reiswig said he still has questions about how the fire started and why regulators did not discover and prevent the hazard, especially in light of the company’s track record of fires at the Conyers plant and a facility in Louisiana.

“There’s going to have to be questions answered about why did inspections not pick this up,” Reiswig told Healthbeat. Thousands of companies store unstable chemicals, Reiswig said, “and most of them seem to manage to not have their plant blow up on a regular basis.”

Reiswig and Sulka said the county will be holding an “after action meeting” in the next month to review all the agencies’ responses and to highlight areas of improvement.

Rebecca Grapevine is a reporter covering public health in Atlanta for Healthbeat. Contact Rebecca at rgrapevine@healthbeat.org.