Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

Over the past decade, fatal opioid overdoses have prematurely ended the lives of over 10,000 Georgia residents. National lawsuits have directed much of the blame for this state and U.S. epidemic at dangerous marketing practices by companies within the pharmaceutical supply chain — which have responded by agreeing to pay tens of billions of dollars in settlements.

The Georgia Opioid Crisis Abatement Trust has begun to use much of the state’s portion of the money to attempt to build on recent reductions in deadly overdose rates. In December, the trust’s overseer, state Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities Commissioner Kevin Tanner, awarded $70 million of settlement money to 128 organizations focused on addressing the public health consequences of the crisis.

Throughout the country, some local and state spending has come under scrutiny for being used on efforts that don’t directly address addiction in hard-hit communities. Many analyses have compared these decisions to state settlements from tobacco companies in the 1990s — money that was supposed to address the public health harms caused by nicotine addiction but was spent on a variety of other uses.

Tanner has said the Georgia Trust is trying to avoid this pitfall by conducting analyses of the greatest addiction needs and trying to fund efforts to address them. The trust’s first 128 grants went to projects that seek to address, prevent, and research substance use disorder.

“This settlement is set up in a very restrictive way to try to make sure that states and local governments spend the money in the way it’s intended,” Tanner told Georgia lawmakers at a meeting in late January. “Which is to prevent harm and to reduce harm from the use of opioids.”

As organizations begin implementing their opioid settlement grants, Georgians who study and research addiction are optimistic about building on the recent state and national progress in preventing overdose deaths.

J. Aaron Johnson, director of Augusta University’s Institute of Public and Preventive Health, helped guide which Eastern Georgia projects received funds. He said that aside from the state’s overdose death rates continuing to decline, it may be difficult to determine the impact of the grants.

“I don’t know how easily visible that will be to the public,” he said. “And certainly it’ll be a long-term impact more than short-term.”

In the meantime, he said, there is more the state could do to battle the decades-long overdose crisis, like implement regulations for recovery residences. Future settlement grants could also be used to reduce the stigma of opioid addiction and encourage doctors to treat it with medication.

Opioid trust funds new and continuing projects

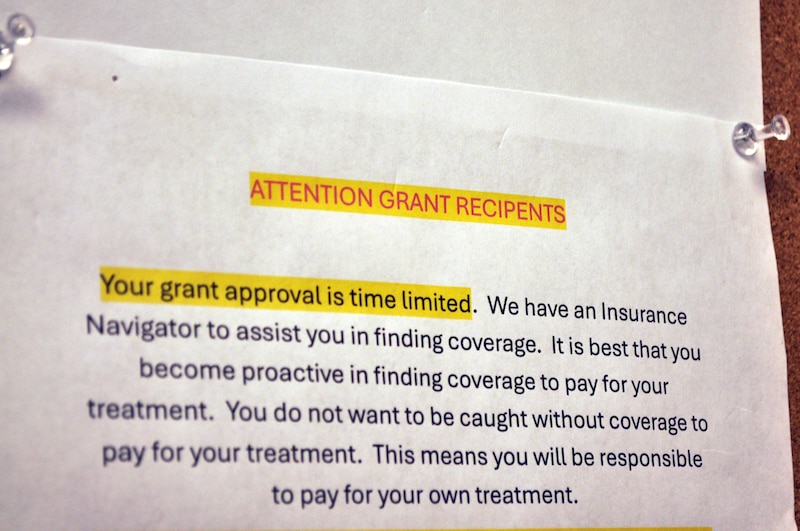

In the waiting room of the McDonough clinic Bright Star Healthcare in early January, there was a sign posted on a bulletin board with the highlighted, red-type, all-caps title “ATTENTION GRANT RECIPIENTS.”

The message was aimed at uninsured patients who, through a state-funded grant, receive addiction treatment there. The clinic is approved to use methadone, an effective medication that reduces opioid withdrawal symptoms. It uses the grant money to subsidize the clinic transportation and treatment costs for 15 patients.

As the bulletin board message went on to detail, it’s intended to be a temporary program as the clinic helps people find insurance options like Medicaid, the federal program for low-income residents. The state funding for the program ended in October, but Bright Star is set to use about $500,000 from the trust to keep the initiative running.

“I don’t want that treatment to end for them — those who can’t afford it,” said George Coley, the clinic’s founder. He added that the funds will also help Bright Star reach out to local hospitals and urgent care clinics about the addiction treatment services it offers.

West of Atlanta in Paulding County, Tony Moon has grown more concerned about the lack of addiction treatment and recovery services for young adults. One of his daughters has struggled with substance use disorder, and he said he couldn’t find organizations near their home to help.

“There was like nothing,” said Moon, who has been in addiction recovery for decades.

The executive director of Rising Sun Recovery, a Hiram-based nonprofit that provides drug-free housing and social services for people with addictions, Moon felt obliged to create services to fill the gap. Over the next two years, he’ll be using just under $500,000 to expand Rising Sun’s services to house and serve clients between ages 18 and 26.

Another addiction recovery nonprofit Moon runs, Paulding RCO, will receive around $360,000 of opioid settlement funds this year to bolster peer services support for these new Rising Sun members and other young people at risk of addiction. The grant will allow Moon to hire full-time staff. He’s excited to be expanding.

“I got in recovery at 20 years old,” he said. “I experienced that, so I help out with creating the environment.”

Moon’s organization is certified by the Georgia Association of Recovery Residences, an arm of a national group that aims to ensure homes are safe for people in recovery. But the credential is voluntary, as the state has yet to implement laws governing how these housing options should operate.

Candice Whittaker, the GARR executive director, said there are likely homes that she hasn’t been in touch with yet that create healthy recovery environments. But other uncertified residences may not be following best practices and could heighten the risk that residents may relapse.

“I couldn’t tell you how many places are operating unethically, because I have no idea,” she said. “Because there’s no way to check.”

Some doctors reluctant to prescribe addiction medication

Johnson, the Augusta University professor, said another factor that could help reduce overdose deaths is increasing the number of providers who prescribe buprenorphine, another medication that reduces opioid withdrawal symptoms. Unlike methadone, most licensed physicians can prescribe it to treat addiction.

But Johnson said there are still pockets of Georgia without doctors who prescribe this gold-standard treatment, often because of stigma related to opioid addiction. He and his colleagues help train physicians on best practices for prescribing buprenorphine, and he often faces hesitancy from health care workers.

“It’s not at all uncommon to have an entire clinic saying, ‘We’re not going to do that because we don’t want those kinds of people in our clinic,’” he said.

Johnson said he didn’t remember seeing many Eastern Georgia opioid settlement applications that would address this issue. Whether it’s through the state’s opioid trust or other efforts, he said Georgia needs to continue addressing providers’ unwillingness to connect their patients to this medication.

“It’s been around for decades,” he said. “I don’t know that you’re going to suddenly change people’s minds, but I do think we’ve come a long way over the last several decades.”

Awardees want to develop tools for long-term recovery

Georgia will likely continue to face challenges addressing the overdose crisis, but Jeff Breedlove said he is optimistic about the future. Breedlove, who’s in recovery himself, has had a hand in the state’s opioid settlement distribution as a former employee of the state’s Behavioral Health Department and as an adviser with the Georgia Council for Recovery.

With the opioid trust’s $70 million set to be distributed in March and another funding application cycle set to open in April, Breedlove said he believes the funded organizations could make substantial progress toward preventing death and anguish related to addiction.

“I don’t feel like any of the awards that were given would embarrass my community or the state of Georgia,” he said.

But there’s more to be done, he said. He and the Council for Recovery are advocating for several bills in this year’s legislative session, including a proposal that would begin state regulation of recovery residences.

To reduce stigma around substance use disorder and ensure the opioid settlements are spent effectively, Breedlove said it’s incumbent upon community advocates, especially those who’ve experienced addiction, to reach out to award recipients and offer their insight.

“That’s when the magic happens,” he said. “When the organization that wants to do good has a relationship with the people they’re trying to do good for, we’ll save lives.”

That’s something BreNita Jackson, executive director of the Decatur women’s residential treatment center Breakthru House, looks to continue doing with her organization’s opioid settlement grant. It’s set to receive just over $100,000 soon.

Jackson said the grant will allow Breakthru to continue its pro-bono work serving women with little financial means. Although recovery can be a private experience, she hopes some in the community may see the ripple effects of her organization’s work.

“To be able to see these women return to a healthy and productive life is what folks should be watching for,” she said. “That they have the tools to be able to maintain long-term recovery.”

Allen Siegler is a reporter covering public health in Atlanta for Healthbeat. Contact Allen at asiegler@healthbeat.org.