Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

Weeks into 2025, measles cases have been reported in communities across the United States, from Georgia to Alaska to New York. As of Tuesday, a single Western Texas outbreak of the vaccine-preventable disease had infected 58 people — over 20% of the number of 2024 U.S. measles cases.

In Georgia, state and county public health officials have worked to respond to a measles outbreak among three unvaccinated metro Atlanta residents, who are all part of the same family. Last week, Gwinnett, Newton, and Rockdale Public Health Departments Epidemiologist Keisha Francis-Christian said her staff had worked with the state Department of Public Health and other local health agencies to contact over 300 people who may have been exposed to the virus.

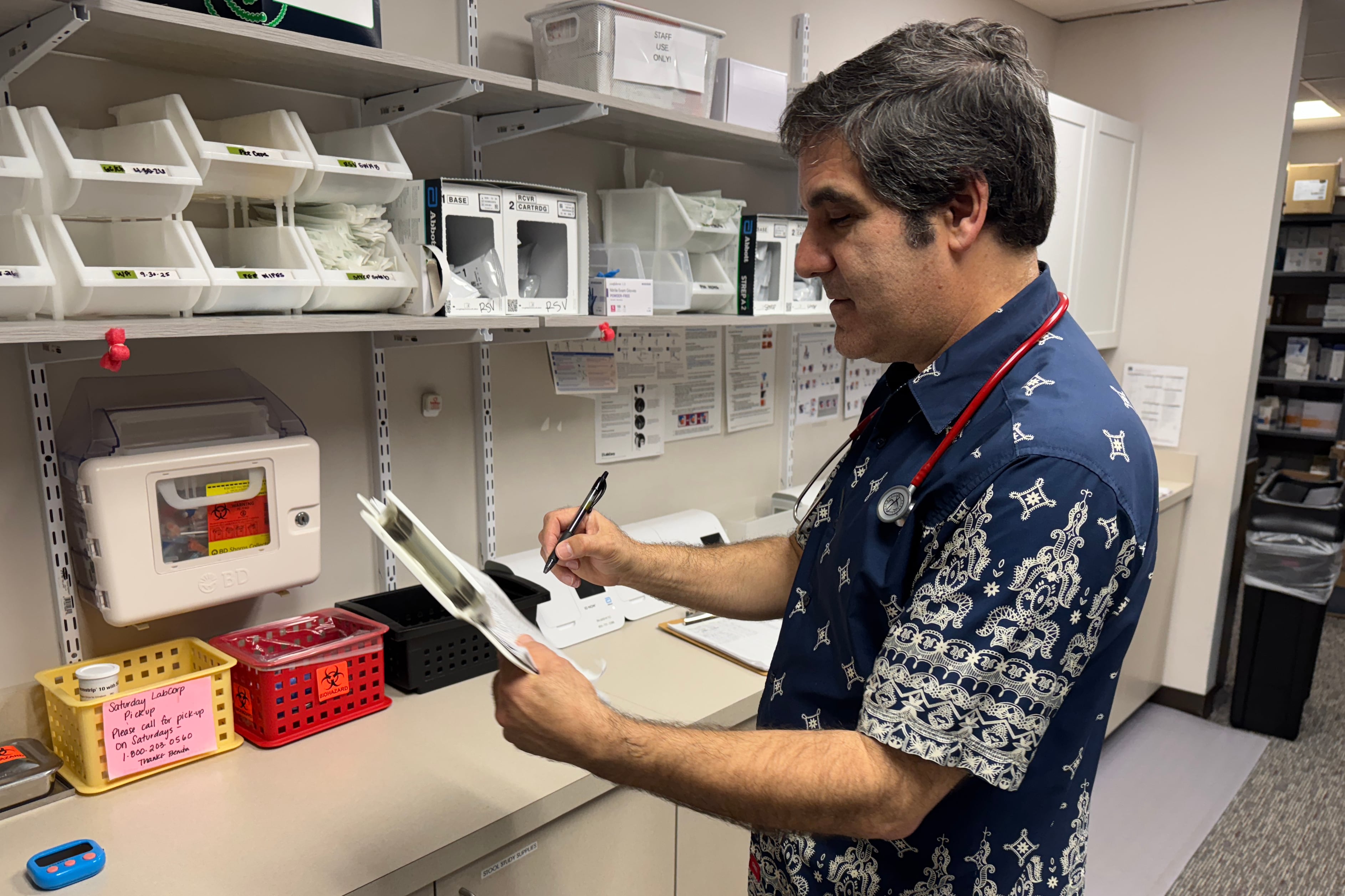

Healthbeat recently spoke with Dr. Roy Benaroch, a Roswell pediatrician and an Emory University adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics, about how the outbreak has affected his practice. He explains how measles can spread, what short-term and long-term effects measles can have on children, and steps parents can take to keep their kids and communities healthy.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How has the measles outbreak impacted your practice?

Certainly, parents are hearing about it. Parents are raising some concerns — I’m glad they know about it. We have not seen a case of measles here, but we’ve been over with the staff how to handle phone calls, triage calls. If someone has symptoms that are suggestive of measles, we have a pathway in place to protect them, to get them evaluated, but also to protect our staff and other patients. Because it is so, so contagious.

The first patient to test positive had apparently gone to three different health care facilities. How does something like that happen?

The initial symptoms of measles may not seem very distinctive. It can begin with an ordinary runny nose and cough — sometimes with red eyes, sometimes with a fever. It’s only several days later, three to five days after that, that the very characteristic rash begins. So when the child is somewhat ill with these less specific symptoms, it may not occur to anyone that it could be measles. There are so many more common viruses out there. There’s plenty of flu out there now, plenty of ordinary common cold viruses. So it can seem very much like something of that nature.

You need to really have your antenna up to be very, very, extra careful with a child who, for some reason — perhaps wasn’t vaccinated or has been traveling outside the country — has big risk factors. You have to think about it, but it’s a needle in a haystack problem.

Fortunately, most Georgians are vaccinated, which provides - if you’ve received both doses - 97%-plus protection, preventing you from catching and preventing you from spreading it. But if you happen to be in a community that has a high proportion of people who are unvaccinated, that’s really asking for trouble once that genie is out of the bottle. If it’s in a community that’s not well-vaccinated, it’s going to spread very quickly.

Do you have concerns our community could be approaching that sometime in the future?

That’s what we’re worried about. Although overall vaccine rates are high, there are pockets, there are communities and neighborhoods where vaccine rates have fallen. And they’re much more vulnerable.

What have some of the conversations with parents lately about measles been like?

Some parents are certainly frightened of it. They want to know what’s going on. They’re concerned that the health department may no longer have the resources they need to tackle this, to track it.

Now, I’m not so sure that’s true. On a national level, there’re concerns about the national leadership and the changes of leadership at the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] and these sorts of things. Those are important, but most of the work being done is really boots on the ground, county health departments. And I’m confident they’re on this. They’ve got the people and the resources to track this and do a careful job.

What else are parents talking about?

Parents want to know, “What should I look out for?” That’s the most common. “How do I know if my child could have measles?” And the first question I’ll ask after that is, “Has your child been fully vaccinated?” If a child’s been fully vaccinated, the risk of contracting measles is just about zero. It’s not impossible. The vaccines are never absolutely 100% protective. But with two doses of MMR [measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine], which all children should have by about 15 to 18 months of age, they’re essentially 100% protected. You have a vaccinated child, you really don’t need to worry about your child catching measles.

Now, you may still worry about your neighbors and your family, but the most important single thing for parents to do it just make sure their kids are fully vaccinated.

Researchers estimate that in the United States, 25% of people who get measles are hospitalized. What is the toll of getting a measles case, and what is the experience of getting a measles case in the United States right now?

If you do get measles, you’re in for a pretty rough time. Very high fevers, terrible cough. About 1 in 4 will be hospitalized for respiratory support and fluids. There’s no specific medication that can be used to treat measles, so it’s just supportive care in the hospital. Unfortunately, even after a case of acute measles, there’s a generalized immune suppression that goes on for several years. So children who make it through measles for several years afterward are more susceptible to many other infections. It’s kind of frightening, but it’s a unique thing that the measles virus does to the immune system.

And then, unfortunately, there is a complication that occurs probably in something like 1 in 3,000 or 1 in 5,000 children who contract measles. Years later, six to 10 years later, [they] can develop an untreatable degenerative brain condition called SSPE [Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis], which will be fatal. That’s not so common, but boy it’s common enough that people should realize that measles is more than a high fever and a rash.

You talked about how effective two doses of the MMR is for kids. As more vaccine skepticism rhetoric has risen at a national level, especially since the Covid-19 pandemic, have you seen parents be more skeptical of vaccines like MMR?

In my practice, the vast majority of families are really relying on their physicians’ advice, and they want to make sure their kids are fully protected. But this does vary by neighborhood. There are neighborhoods and communities where there’s more vaccine distrust. We know nationally, there’s data showing families are looking into vaccine exemptions, for instance, so their kids can go to school without being fully vaccinated. There are state legislatures that are considering withdrawing school vaccine requirements. And it’s unfortunate because that’s really being driven by a lot of fear and misinformation. If families were getting the best information available, the vast majority would want their kids to be vaccinated. But there’s a lot of fear, and it’s a little bit hard to fight that.

You talked a little bit about talking to parents who may worry about getting their children vaccinated. What are those conversations like?

For the measles vaccine in particular, especially since it’s been on the news, you can share with them the numbers. You can say, “This is what happens.” Measles, we know, is one of the most infectious, contagious illnesses that we’ve ever experienced. If a child who has the measles has been in a room — even after they’ve left the room for two hours, the air in the room literally can still transmit measles. Measles is much more contagious than Covid or flu. And at the same time, it really can be a serious illness. It can put kids in the hospital. There are short-term and long-term complications.

And then you can say this is the vaccine. It has been around for a very, very long time. The rate of [lasting] side effects is very, very low. You can get mild symptoms that will occur maybe even a week later. But then they go away, and your kiddo is protected. And the protection, having had two doses of the vaccine, lasts the rest of your life with no important common side effects. Rare side effects can happen, but they’re really rare. I can say in my career, which is getting close to 30 years, I’ve never seen a serious complication from any vaccine. What I have seen [are] children sick with illnesses that could have been prevented with vaccines.

Earlier in this conversation, you said you thought the state and local health departments had done a really good job investigating cases. But you also referenced uncertainty around federal public health funding.

Both the state and local health departments get a lot of their funds from the federal government. If funding changed so these local health departments and the state health department can’t carry out these types of investigations, what risk does that pose for the communities you serve?

People have gotten used to safe food. People have gotten used to knowing when there is illness in the community — how to prevent it, and how to avoid it. We’ve all gotten complacent about the role of public health. When the public health system is working, we don’t notice it very much. That means you have an effective public health system, it means you can just go about your life without a good deal of worry.

But if the funding dries up or if the funding is just unreliable — just not knowing if a grant is going to come through — that could really lead to problems with tracking, with employment, with having the right people in the right place being able to jump in to investigate outbreaks, and to educate the public about how to stay healthy. I think right now, there’s just a lot of uncertainty.

Public health affects all of us. This isn’t something that’s just for certain neighborhoods or underserved neighborhoods. It doesn’t matter how wealthy you may be, or how fancy your house is. You need clean air, you need a dependable food supply, clean water. These are very, very basic things that we’ve been able to take for granted for so many years. But the reason these are reliable is because of public health, and [workers] quietly doing their jobs.

Allen Siegler is a reporter covering public health in Atlanta for Healthbeat. Contact Allen at asiegler@healthbeat.org.