Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free New York City newsletter here.

Gov. Kathy Hochul revived New York City’s congestion pricing plan on Thursday, throwing her support behind a program that aims to reduce pollution, fund the public transit system, and improve residents’ health.

Officials framed the return of congestion pricing as a historic win for the environment and for public health. By taxing vehicles entering parts of Manhattan, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority plans to generate billions of dollars to fund transit improvements throughout the city, from extended subway lines to new electric buses and increased accessibility at subway stations.

“New Yorkers want cleaner air, safer streets, and a transit system that works for them,” Janno Lieber, chief executive of the MTA, said at a press conference.

Hochul unexpectedly paused congestion pricing in June. She now faces a brief window to implement the plan before the inauguration of President-elect Donald Trump, who has vowed to kill it.

The plan has faced additional opposition, including lawsuits from New Jersey and local truckers. Some local officials and community organizations have also raised concerns that vehicles diverted from Manhattan will further pollute outer boroughs like the Bronx. The MTA has pledged to fund mitigation measures, including electric truck charging infrastructure, air filtration units in schools near highways, and more green spaces.

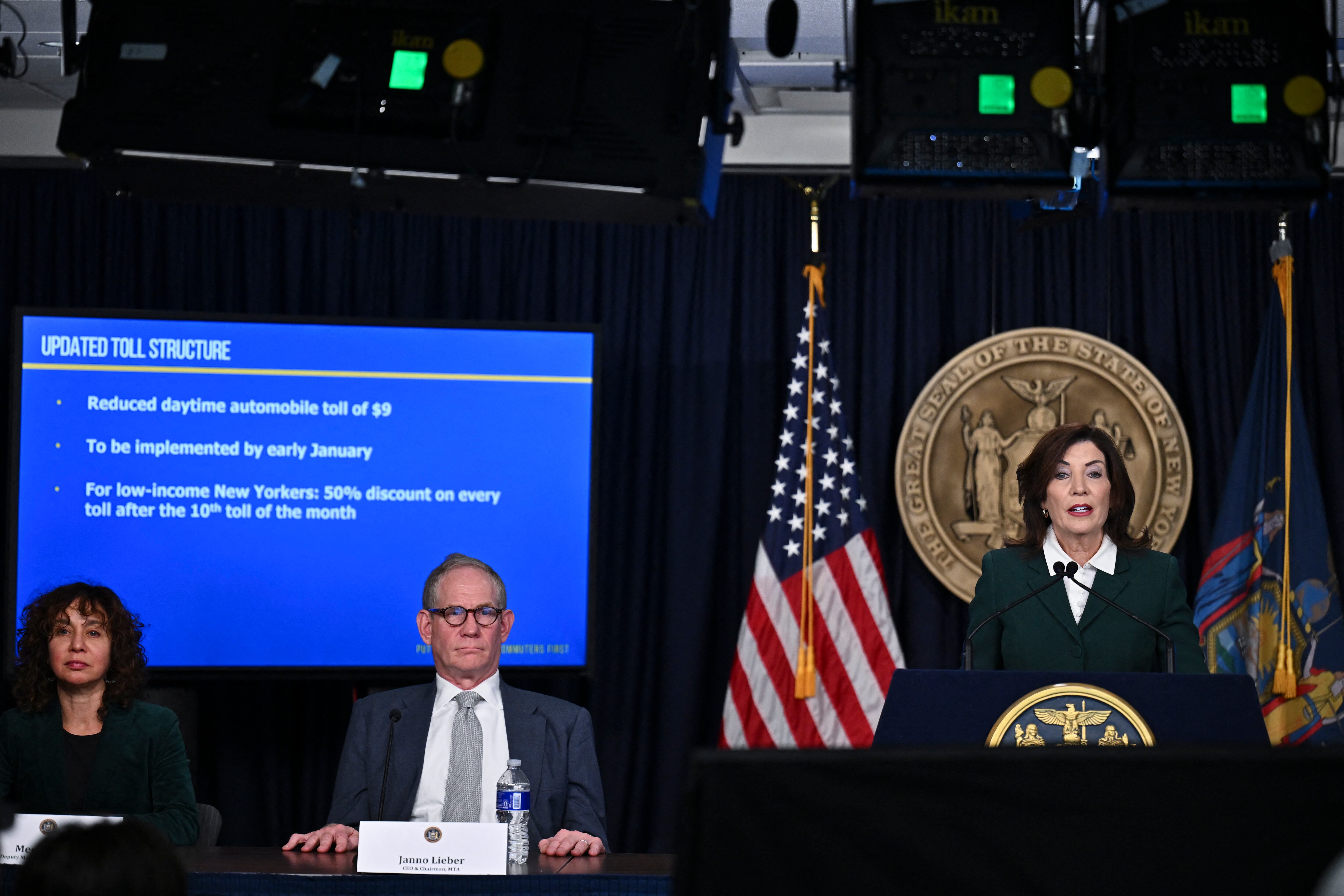

The congestion pricing program has three main objectives, Hochul said: to enhance the public transit system, to reduce gridlock — protecting pedestrians and clearing the way for emergency vehicles — and to improve air quality. Under the new plan, most passenger cars would be charged $9 to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street during peak hours, a reduction from the $15 fee previously proposed.

New York City Deputy Mayor for Operations Meera Joshi likened the congestion pricing plan to the city’s decision to ban smoking in bars and restaurants in the early 2000s — and its compounding health impacts on future generations.

“Our restaurants are thriving, our air is cleaner, and we’ve saved tens of thousands of lives from lung cancer. More importantly, we created a healthier new normal for this generation,” she said. “We once questioned this big culture change, and now we celebrate it. That’s how this moment will be remembered, too.”

Congestion pricing programs have existed for decades in other cities across the world, including in London and Stockholm, and research suggests a link to health benefits. Both cities saw significant reductions in pollution levels after implementing congestion pricing, and in Stockholm, rates of asthma-related doctor visits among young children fell by 6 visits per 10,000 children in the congestion zone, relative to control areas.

Danny Pearlstein, policy and communications director for the Riders Alliance, an organization that advocates for transit users, said congestion pricing would have a clear positive impact on New Yorkers’ health.

The program would likely deter car trips into Manhattan, improving air quality and allowing emergency vehicles to navigate the city more quickly, he said. And its revenue would bring significant investments in a more efficient public transportation system.

“Better transit is tied to all sorts of good health outcomes, mostly because it gets people walking,” he said.

But some local officials and advocates have raised concerns about the spillover effects of the plan on outer boroughs. An environmental assessment conducted by the MTA in 2022 found that congestion pricing could lead to a slight increase in pollution in the Bronx, with added truck traffic on the Cross Bronx Expressway.

The MTA has pledged to fund mitigation measures in the Bronx, earmarking $20 million for an asthma center and case management program and $15 million to replace diesel-powered trucks at the Hunts Point Produce Market. Officials stressed that those and other mitigation measures would remain fully funded under the new plan.

“They need it,” Hochul said of areas like the Bronx. “This is a community that needs the assistance, and I’m proud to deliver it.”

Arif Ullah, executive director of South Bronx Unite, an environmental justice nonprofit, said his organization supports congestion pricing in principle — but not at the cost of further polluting the South Bronx, which has among the highest childhood asthma rates in the country.

“We welcome all pollution mitigation measures for the South Bronx and for any pollution-burdened community, but they should not be dangled in front of us as a bargaining chip for adding more pollution to the area,” he said.

It’s not clear how the revised congestion pricing plan might alter the MTA’s projections about traffic flows into the Bronx, Ullah acknowledged. But any local increase in pollution due to congestion pricing would be “unacceptable,” he said.

South Bronx Unite began monitoring local air quality a few years ago through dozens of sensors, and Ullah said the organization plans to collect data on the potential impacts of congestion pricing if it is enacted.

New York officials still require final federal approval before congestion pricing can begin, and multiple lawsuits against the plan are pending.

Eliza Fawcett is a reporter covering public health in New York City for Healthbeat. Contact Eliza at efawcett@healthbeat.org .