This story was originally published by Epicenter NYC. Sign up for their newsletters here.

Ed Manchess can’t wait for the pernil, or slow-cooked pork roast, his team is serving up for Christmas at the Bronx-based harm reduction center he directs. It has less to do with Manchess growing up alongside boricuas in Uptown Manhattan — and more that, for some, this kind of gathering could mean the difference between life and an overdose death.

“Holidays are traumatic for people that use drugs,” Manchess said. Being in community at a traditional meal can help, he says.

Drug overdose rates tend to spike by about 22% during in December and January around the holidays, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Holiday stressors lead some people to increase their substance use as a coping mechanism, or for people in early recovery to relapse.

Not everyone can celebrate a decline in overdose rates

In October, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene released data that sounded off a celebratory note — drug overdose deaths in NYC had declined in 2023 for the first time since even before the pandemic.

But this good news was mostly for white New Yorkers, for whom overdose deaths fell by 14%. They rose 2% for Latinos in the city and stayed just as high for Black New Yorkers. Older Black New Yorkers, aged 55 to 84, face the greatest risk overall compared to other groups: 115.5 deaths per 100,000 residents. The Bronx continues to carry the highest overdose death rate of all boroughs.

Advocates rattle off the social determinants for high overdose rates in the most vulnerable New Yorkers: poverty, housing instability, less access to health care, and policing, to name a few.

How stigma affects older at-risk New Yorkers

Stigma and isolation are less visible but crucial factors. Kristin Goodwin, associate vice president of Harlem United‘s Integrated Harm Reduction department, points out that the vast majority of people who have a fatal overdose are using drugs alone.

And contrary to popular misconception, most are not overdosing on the streets. They are most often in their own home, or the home of someone they know — but where no one’s around to respond in the case of an overdose.

“What that tells us is that people are still using unsafely, largely because they’re afraid to talk to people in their lives about their substance use,” Goodwin said.

Her department sees a hesitance to seek healthcare, especially in their clients aged 50 and older. It might sound counterintuitive: This is the age group more likely to have chronic health issues like diabetes and heart disease, who could really use regular doctor checkups.

“Some of that is stigma related, where they’re afraid to talk to a doctor about their other health issues because they’re afraid the doctor is going to shame them for their substance use,” Goodwin said. “So they just disconnect themselves from the health care system in general.”

Dr. Carolann Slattery, the chief clinical officer at the nonprofit Samaritan Daytop Village, says adults aged 55 and older they often isolate themselves, which limits access to care and increases health issues like chronic pain. These conditions also worsen due to systemic addiction to opioids and other substances.

“Do we still have stigma? Of course,” Slattery said, adding that groups like Samaritan are working hard to reduce the related racial and ethnic discrimination around it. “But unless we get providers to understand cultural competency and incorporate trauma-informed care, the message will fall short.”

How policing makes things harder

Policing also plays a role in limiting access to treatment in places like the Bronx. Just a decade ago, Harlem United’s clients were still getting arrested for carrying clean syringes, Goodwin said. While that has stopped, there’s still an obvious stigma toward people who use drugs because of the legality around it.

Police competency around stigma varies — even from one precinct to another in Harlem. Goodwin has seen officers from East Harlem’s 25th precinct escort people to the overdose prevention center and engage with staff. Meanwhile, one precinct in Central Harlem has a different training culture. These differences impact access to substance use treatment and overdose prevention.

“In marginalized communities, people are fearful of the police, so accessing a place like a harm reduction center to get whatever goods they may need [is difficult],” Manchess said. “It really appalls me that you don’t see this on Park Avenue, you don’t see this in Central Park, but you see it in all the parks in the Bronx — kids having to climb over syringes and stuff like that.”

But policing of mostly Black and Latino New Yorkers doesn’t stop what Manchess, who lived in the Bronx for years, calls an open drug market: “Go to the hub over there by 149th Street or the North Bronx near Valentine Ave — it’s like they run the community,” he said.

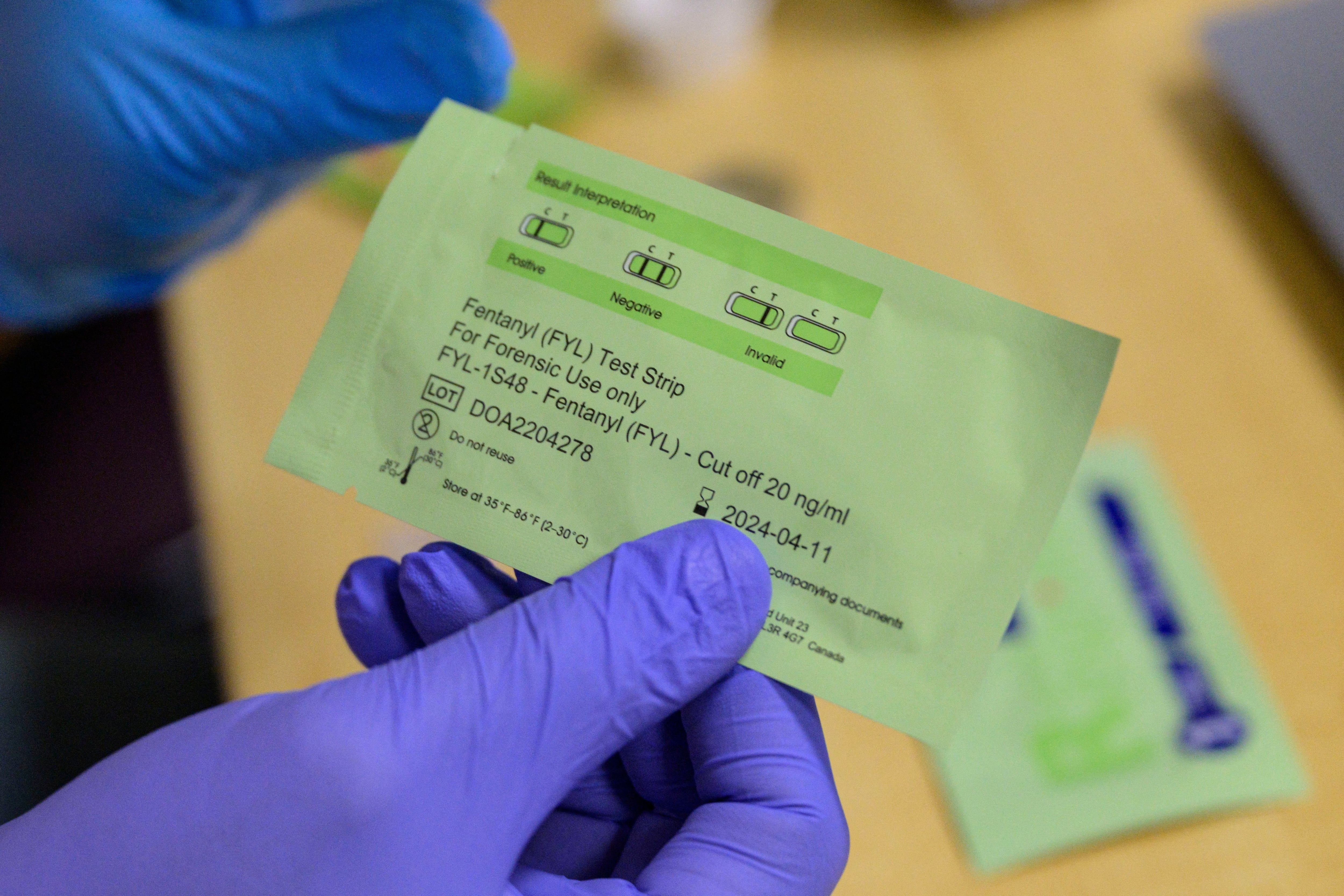

Moreover, the market carries an unsafe drug supply. This includes often fatal drugs like fentanyl, carfentanil, and xylazine. He says the other day, the BOOM!Health nonprofit got a sample through drug testing that was 21-25% fentanyl.

“That’s a death sentence for anyone without a tolerance,” Manchess said.

Hardening the lines of treatment

While Black and Latino New Yorkers in Uptown Manhattan also continue to struggle with some of the highest overdose rates, gentrification plays a role in keeping it that way. Goodwin says the large push against substance use treatment programs and street outreach has come largely from new Harlem residents. They claim the presence of substance use treatment programs is behind a perceived rise in crime.

“It’s very hard to argue, because it’s not good cause and effect, but they’ve convinced elected officials that there’s merit to that argument,” Goodwin said.

Notably, Gov. Kathy Hochul has hardened her stance on funding overdose prevention centers, as Politico has reported. This is despite the only two overdose centers in New York (which are in Washington Heights and East Harlem and are managed by nonprofit OnPoint NYC) having helped thousands of people since opening in late 2021. It’s also despite the state Opioid Settlement Fund Advisory Board twice recommending that the Hochul administration allocate money to these centers.

What loneliness has to do with it

Manchess knows too well how stigma can compound isolation to set someone on the path to a possible overdose. He started using heroin at age 13 in Washington Heights. He recalls being introduced to drugs by older peers.

“There must have been something missing in my life,” Manchess said. “So many people who use drugs are seeking something — a sensation, an escape, a way to detach from pain or trauma.”

It quickly spiraled into addiction.

“Heroin allowed me to detach emotionally, even mentally, from traumatic events in my life,” he said. “But it also isolated me from my family and the world around me.”

The stigma surrounding drug use made it harder to get help. “In that life, it’s so hard to trust people,” Manchess said.

Stigma can hinder someone from getting care and others from caring for someone who needs help. Xylazine creates sores and wounds. And nobody wants to treat these wounds because of the associated stigma: “Ask anybody who uses drugs how they’re treated when they walk into a medical institution — it’s dehumanizing,” Manchess said.

He only started his journey to recovery, peer leadership, and ultimately leader in harm reduction because of an arrest. The judge gave him an ultimatum: time in prison or in a substance use treatment program. He chose Samaritan Daytop Village.

More than three decades later, Manchess is leading harm reduction efforts focused on meeting people where they are — providing clean needles, overdose prevention kits, and nonjudgmental support.

“We need more spaces where people can feel safe to talk,” Manchess said. “People are carrying so much pain. They don’t just use drugs because they want to — it’s often about what’s been taken from them, or what they’re trying to forget.”

It never fails to hurt him to see fellow New Yorkers walk by people who seem to be overdosing. “It’s ‘there go those junkies again,’” Manchess said. “I’m just hoping that somehow, someday, somebody can deliver the golden message: ‘Stop for a moment and help your fellow man.’ People that use drugs are people, and they deserve to live, too.”