Sign up for Your Local Epidemiologist New York and get Dr. Marisa Donnelly’s community public health forecast in your inbox a day early.

Immigration, one area experiencing significant policy change, is inextricably linked to public health. News of ICE raids has been all over the media, but what does that mean, and how do they affect New Yorkers?

Regardless of one’s political stance on immigration, understanding the health consequences and downstream effects of changing policies is crucial for protecting community health. It’s important to understand the data and look at the bigger picture—that’s what I’m here to do.

Let’s dig in.

What are ICE raids?

ICE stands for the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, a federal law enforcement agency whose mission is to enforce immigration laws within the United States and investigate activities like human trafficking, smuggling, and visa fraud.

“ICE raids” are operations conducted by ICE officers to find people who don’t have legal immigration status or have broken immigration laws. When ICE raids happen, undocumented immigrants are often detained and deported.

What changed last week?

Since 2011, ICE has not been allowed to arrest people in “sensitive locations,” including hospitals, schools, daycare centers, and places of worship. This policy was established to maintain people’s access to essential services, like medical care and school, regardless of immigration status.

Last week, the policy protecting sensitive locations from ICE raids was revoked. This means officers can now arrest people at places like hospitals and schools. But, under protections from the 4th Amendment, ICE cannot enter the private spaces of hospitals (like patient areas) or schools without a judicial warrant.

Who does this affect in New York?

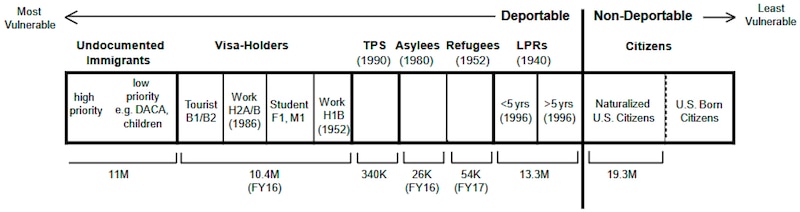

Immigration status is not a simple yes-no but rather exists on a spectrum.

As this graphic shows, many U.S. residents are not citizens and live here under work visas, green cards, or are somewhere in the process of gaining citizenship. Reports of raids and deportations can instill fear in all of these groups and lead to avoidance of essential services.

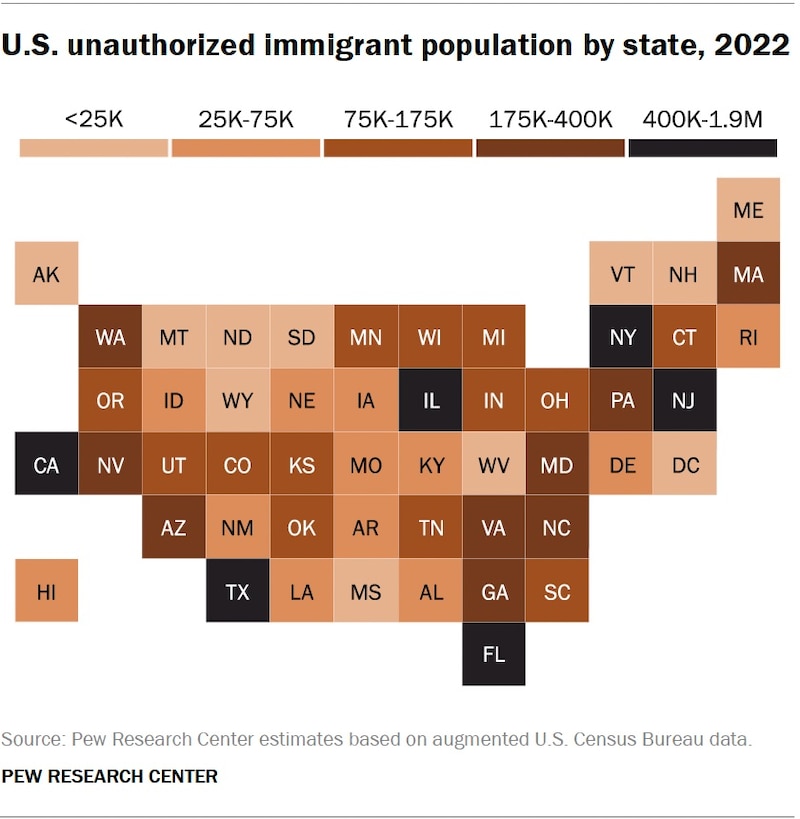

Among the 3.1 million immigrants in New York City (about 1 in 3 New Yorkers), around 400,000 are undocumented with around 50,000 of those children. Pew has estimated that 650,000 are undocumented across the state (1 in 4). New York is one of the most diverse parts of the country, as shown in the map below.

ICE raids have profound health effects on individuals and communities

There is a direct health impact of trauma. (More on that in a moment.) But fear alone can lead people to avoid seeking health care, such as not calling 911 during emergencies or delaying treatment until an illness becomes severe. Hospitals and ERs are critical locations for catching and treating diseases early. When care is delayed, treatments are more costly and more deadly.

- In 2023, after Florida passed a law to require hospitals to ask for immigration status, 66% of noncitizens reported increased hesitation to go to the hospital (compared to just 27% of citizens).

- After a similar law was passed in Alabama, visits to county public health clinics among Latino adults decreased by 25%.

But this doesn’t just impact the health of individuals who are undocumented, it affects the health of the communities as well.

- Infections have the chance to spread more widely. In Los Angeles, research shows that patients who fear immigration authorities are about three times more likely to delay seeking care for tuberculosis. Without treatment, TB is contagious and can lead to severe illness or death.

- Mental health impacts, like toxic stress, are not limited to undocumented immigrants; it can affect the community at large. A 2008 raid at an Iowa factory resulted in the detention of 400 people, spreading news throughout the state. A study found that in the 37 weeks following the raid, there were more Hispanic babies born with low birth weight due to stress in mothers across the community, while birth weights in babies born to white mothers remained stable.

- Delayed care among extended families and communities who step up and offer support. In one study, a clinician described an example: “(My patient)…from Uganda with HIV/AIDS and end-stage renal disease was unable to consistently keep appointments for dialysis because she needed to work to support her sister’s two children after (her) sister was arrested by immigration."

Children are especially vulnerable

There are many “mixed” status families. But families tend to behave according to the person with the least documentation—and they may forgo services that children who are U.S. citizens are eligible for.

Traumatic events like watching a parent or classmate get arrested and deported can have lasting effects on children. Even outside of acute events like raids, the prolonged stress from fear of deportation, potential family separation, and difficulty accessing essential services like health care and education can lead to toxic stress in children.

Toxic stress is the prolonged stress response in the brain and body (e.g., increases in heart rate, blood pressure, and stress hormones like cortisol). It has long-lasting effects because it prevents normal development of neural connections in the brain.

We are hearing of families who are afraid to take their kids to school out of fear of deportation. Missing school can deprive students of more than just learning—for many, schools are one of the primary ways kids access nutritious meals, mental health services, and other essential support.

These challenges are compounded by the short- and long-term financial impacts on families who lose a primary income provider due to deportation or detainment, as well as the heightened risk of children being placed in the child welfare system.

How can we support children?

Children going through immigration and separation experiences need extra support. This document from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network gives recommendations for caregivers to address the needs of children going through these events. Some key points include:

- Create a safe and supportive environment: Speak calmly, reassure children, and provide comforting actions like hugging (with permission) or reading.

- Address emotional and behavioral needs: Children may exhibit behaviors like irritability, clinginess, or withdrawal. These could be signs of trauma, not “bad behavior.” Encourage calming or enjoyable activities like drawing, games, or music.

- Foster family and cultural connections: Support contact with family members when possible (e.g., visits, calls, or video chats). Avoid speaking negatively about family. Try to celebrate and honor cultural traditions and foods.

- Provide trauma-informed care: To help manage stress, teach calming exercises like slow breathing or muscle relaxing. Limit exposure to distressing media while providing accurate, age-appropriate information about their situation.

What can educators do?

All children should have access to education. In New York, the State Education Department and the governor and attorney general’s offices have offered guidance for New York schools to help continue providing equal access, regardless of immigration status. Key points include:

- Protecting student information

- The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act prohibits disclosing personally identifiable information without parental consent (except in some legal circumstances). Student information should only be released to federal or local law enforcement when legally compelled (e.g., judicial warrant or subpoena).

- Avoid collecting immigration or citizenship status information, and anonymize such data when collected for specific programs.

- Do not collect (or ask for) Social Security numbers.

- Responding to law enforcement requests

- ICE or law enforcement officers should only be allowed on school property when there is a judicial warrant, and the school district attorney should always be consulted.

- Supporting families affected by immigration enforcement

- Encourage families to update emergency contact information, including secondary contacts.

- Schools may recommend legal and advocacy organizations to help plan and establish standby guardianship.

What can clinicians do?

Many immigrant and undocumented people may be hesitant to seek medical care. Clinicians, whose primary role is to ensure patient safety, can take actionable steps to support these communities within the clinical setting. There are different laws for every state, but here are guiding principles for New York:

- Ensure confidentiality and reassure patients that their immigration status is confidential and protected under HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act).

- Avoid collecting or documenting any non-required immigration-related information, especially within patients’ medical records. (This is required in Texas and Florida, but not in New York.)

- Stop asking for Social Security numbers.

- Know the legal landscape and understand patients’ rights, such as their right to health care regardless of immigration status, and communicate these rights to patients.

- Stay informed about policy, like New York’s Executive Order 170, which prohibits inquiring about or disclosing immigration status unless legally required.

- Train staff to respond to ICE or law enforcement inquiries. If ICE does show up:

- Obtain the officer’s information (name, badge number, etc.).

- Ask for any supporting documents (e.g., judicial warrant or subpoena). Make copies or take photos of these.

- Immediately call the hospital’s Risk Management Office or immigration liaison. They can contact proper legal channels and advise on the next steps.

- If officers take action before immigration liaisons can be contacted, take videos and photos of any enforcement actions.

- Do not try to actively help a person hide from ICE.

Providing compassionate, trauma-informed care is always critical, especially for patients who may have experienced fear or discrimination due to their status.

Bottom line

Immigration raids have big impacts on the public’s health—both individually and for communities. As a community, we can take action to lessen health impacts. When we protect the health of our most vulnerable community members, we protect everyone’s health.

Love,

Your Local Epidemiologist

Dr. Marisa Donnelly, a senior epidemiologist with wastewater monitoring company Biobot Analytics, has worked in applied public health for over a decade, specializing in infectious diseases and emerging public health threats. She holds a PhD in epidemiology and has led multiple outbreak investigations, including at the California Department of Public Health and as an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Marisa has conducted research in Peru, focusing on dengue and Zika viruses and the mosquitoes that spread them. She is Healthbeat’s contributing epidemiologist for New York in partnership with Your Local Epidemiologist, a Healthbeat supporter. She lives in New York City. Marisa can be reached at mdonnelly@healthbeat.org.