Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free New York City newsletter here.

Recent diners at a Lebanese restaurant in Manhattan may have been exposed to the highly contagious hepatitis A virus, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene announced on Friday.

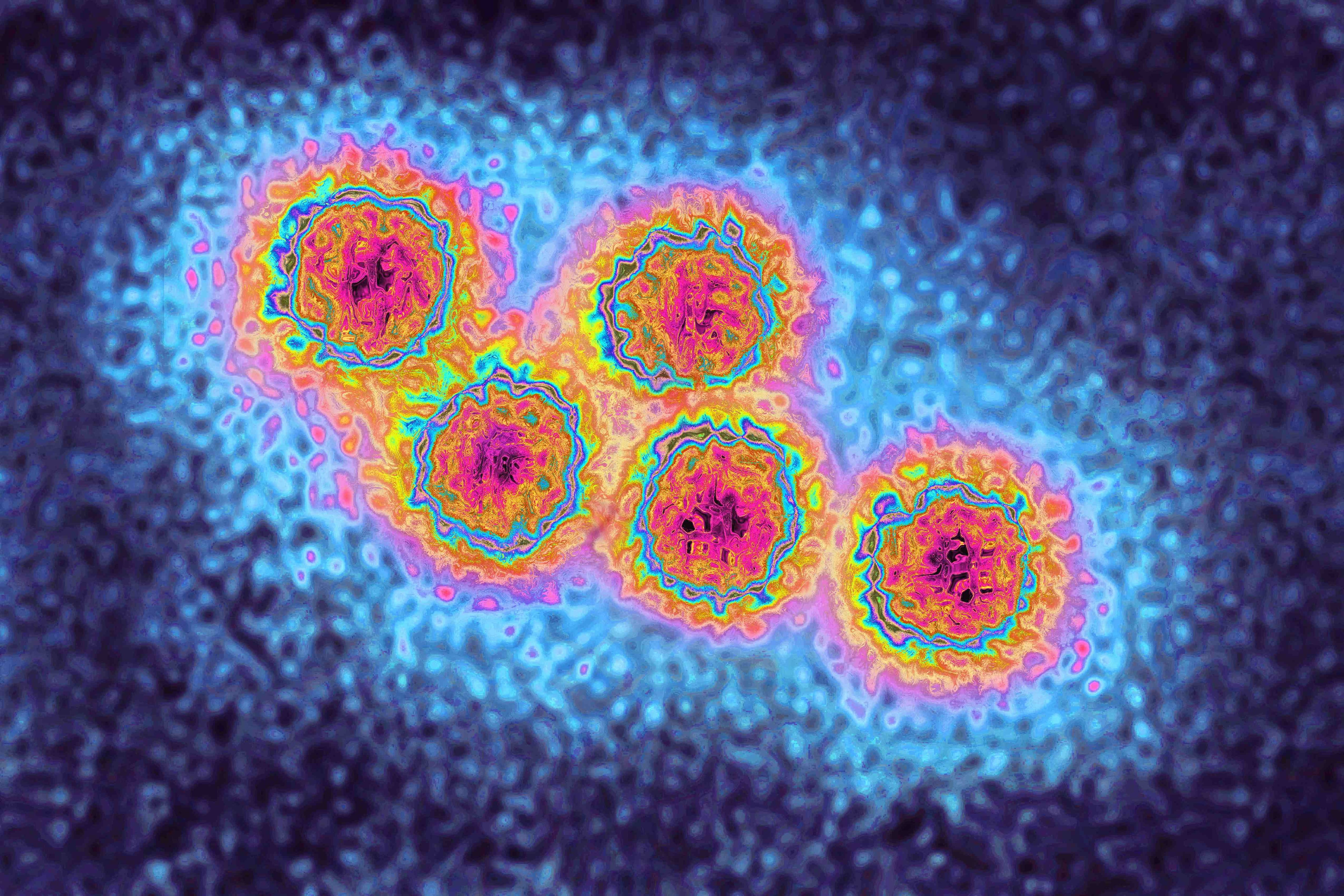

The Health Department was recently notified of a case of hepatitis A, an inflammation of the liver, in a food handler at ilili Restaurant at 236 Fifth Ave. in the Flatiron District, according to the agency. No other cases of illness have been identified.

The Health Department advises anyone who dined at or ordered takeout from the restaurant between Jan. 31 and Feb. 9 to get a hepatitis A vaccination, if not already vaccinated. New Yorkers seeking a vaccine can contact their health care provider, search for a vaccine provider on the NYC Health Map, or reach out to NYC Health + Hospitals, the municipal health system.

“We are urging these restaurant patrons to consult with their providers and get the hepatitis A vaccine as a precautionary measure,” Dr. Michelle Morse, the acting health commissioner, said in a statement. “If people experience symptoms like yellowing of eyes and skin, fatigue, abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea, they should see a doctor immediately, especially if you have not had two doses of the hepatitis A vaccine.”

Additionally, the Health Department encourages anyone who ate the restaurant’s food between Jan. 17 and Feb. 9 to monitor for symptoms of the virus for seven weeks following their meal. Other New Yorkers should stay up-to-date on vaccination recommendations, and to thoroughly wash their hands to limit disease spread, Morse said.

In a statement on Facebook on Friday, ilili said the restaurant learned on Wednesday that a kitchen employee had tested positive for hepatitis A. The restaurant said it was working with the Health Department, had repeatedly deep-cleaned its kitchen and will ensure that staff has access to free testing and vaccination.

The hepatitis A virus is spread through close person-to-person contact or by eating contaminated food or drink. The virus usually causes a mild, short-term illness, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Those infected may feel sick for a few weeks or months, but typically do not have lasting liver damage. However, in rare cases, the virus can cause liver failure or death — outcomes that are more common in older people or in those with chronic liver disease or other serious health issues.

Symptoms of hepatitis A usually appear two to seven weeks after exposure and can include dark urine, diarrhea, fatigue, fever, joint pain, loss of appetite, nausea and jaundice, according to the CDC. Some infections are asymptomatic.

The best way to prevent a hepatitis A infection is through vaccination, which confers long-term immunity, according to public health authorities. The CDC recommends vaccination against hepatitis A for all children ages 12 to 23 months, all children between the ages of 2 and 18 years who are unvaccinated, and all people who have increased risk factors for the disease.

The chef Philippe Massoud opened ilili about two decades ago. In 2008, The New York Times described the upscale restaurant as “probably the most ambitious Middle Eastern restaurant, in terms of scale and décor, in New York.” On Friday, the restaurant was promoting a $155 per person four-course prix fixe menu for Valentine’s Day.

Eliza Fawcett is a reporter covering public health in New York City for Healthbeat. Contact Eliza at efawcett@healthbeat.org.