Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free New York City newsletter here.

As New York City confronts a self-diagnosed maternal health crisis, community organizations are offering at-home support for new and expecting parents, including mental health care.

Demand for the services has increased since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, but funding remains a concern. And while every birth story is different, there is a common theme for many: inequities.

About two dozen New Yorkers die related to pregnancy or childbirth in New York City each year. Three in four Black maternal deaths are ruled as preventable by the health department’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee. For white women, it’s about half, said Dr. Michelle Morse, acting commissioner of the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

“We’re concerned about the magnitude of the inequity here in New York City,” Morse told Healthbeat. “Somehow we are selectively choosing to save the lives of some women over others. We need to look at what is driving that.”

While most birthing experiences in New York City are healthy, Black women are nine times more likely than white women to die during pregnancy or childbirth, according to the mayor’s office. While this disparity can change slightly depending on when it’s measured and with what reference point, nationally, the disparity is lower, at about three times more likely, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hispanic women in New York City are three times more likely than non-Hispanic white women to die of a cause related to pregnancy or childbirth.

Pregnancy-related deaths, many of which are preventable, have become a priority for the New York City Council. Suicide and overdose are the leading causes, Morse said.

“We need to do an even better job screening for substance use and mental health issues, including risks for suicide, looking at perinatal mental health and anxiety disorder,” she said.

While leaders of community-based maternal health organizations agree that the mental stress that accompanies pregnancy – and the taboo of talking about it – is a top worry, birth emergencies are also a persistent concern.

In September, a pregnant woman who emigrated from Latin America six years ago arrived at Brooklyn’s Woodhull Medical Center, one of 11 city-run public hospitals. Bevorlin Garcia Barrios, 24, arrived at the hospital with nausea and stomach pain. She was sent home. Three days later, she was back, this time to deliver her baby. A day after being admitted, she died following an emergency C-section. She was the third woman to die during childbirth at the hospital since 2020.

City increases access to doulas and midwives

Numerous community-based organizations and city programs offer health support to eligible expecting parents. In December, for the first time, the city funded a $1.5 million guaranteed income program for 161 pregnant women experiencing homelessness.

In recent years, the city and state of New York have increased access to programs that provide at-home care, such as midwives, who provide medical birthing support, and doulas, who provide non-medical support.

The Brooklyn Communities Collaborative, a health equity nonprofit, recently awarded nearly $1 million in grants to 10 community-based organizations that offer a range of maternal health services, from mental health and community outreach to providing diapers and paternal and grandparent education for low-income families.

Around the same time Barrios arrived in New York, a Venezuelan woman moved to the city. Nearly six years later, in 2024, she was also pregnant.

Nervously nearing her unexpected due date, with no family in the city, the Brooklyn resident and paralegal found herself in one of New York’s Presbyterian hospitals. Feeling alone in the pregnancy, she was asked if she’d like a doula.

“What is a doula?” she wondered, recalling the experience for Healthbeat, requesting her identity be withheld over fears about her immigration status.

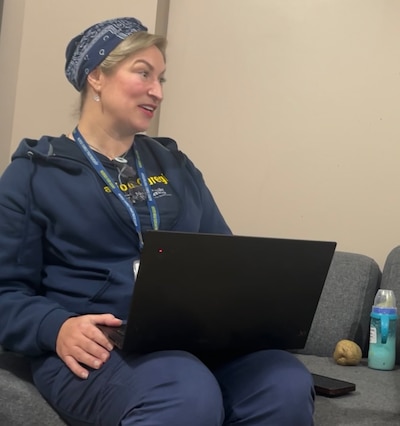

The woman was partnered with Leigh Bearden, a registered nurse specializing in maternal child health through the city’s Medicaid-eligible Nurse-Family Partnership program. The RN helped ease her anxieties, and she gave birth to a healthy boy.

Bearden was like a therapist, a doula, and a second mom. Eleven months after giving birth, Bearden still meets with her regularly. On a January afternoon, she fielded questions about the normal struggles of finding daycare and returning to work.

“A person who is pregnant,” Bearden’s client said, “you need economic support, that’s true, but you need emotional and mental support because being pregnant is a process.”

The woman’s experience going from feeling isolated and ill-equipped for an unexpected pregnancy to a successful hospital birth and raising a toddler shows what the city’s programs are intended to do.

Access to health care key factor in maternal mortality

“Most births occur in hospitals,” said Deborah Kaplan, a former assistant commissioner in the city’s Bureau of Maternal, Infant and Reproductive Health. “Hospitals are not the best places to give birth for most people, but birth has been fully medicalized.”

An increased scrutiny of hospital births led the city to launch a doula initiative in 2022, providing free services through Medicaid. The city’s New Family Home Visits programs, which includes NFP and the doula initiative, served nearly 20,000 Medicaid-eligible families since 2022, including about 9,500 in 2024, according to the health department.

City-run services fill up and face financing and staffing complications. Through Medicaid, some programs like NFP have an income requirement.

Research suggests New York City’s maternal health disparity is mostly independent of socioeconomic status, a frequent misconception. It is actually linked to structural racism, policy decisions, and access to healthcare.

Kaplan, who teaches about the context of race in maternal health at the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health, says expanding Medicaid access to doulas isn’t enough. The city, she says, needs to diversify the staffing of such programs so that at-home providers are more representative of the people they serve.

Along with city council members, current and former health department officials like Kaplan and Morse praise community-based organizations for their maternal health work.

The Alex House Project, a Boerum Hill-based organization, received over $150,000 from the BCC grant. Demand for the small team’s services have doubled to nearly 150 mothers or expecting parents since the start of the pandemic.

Samora Coles, AHP’s founder and executive director, said that public figures’ conversation on the issue helps drive progress. But organizations like hers that are trying to create their own resource pipeline through grants and donors independent of the city, need more resources, she says.

“We know what to do, but there is not both the political will, the long-term leadership you need, and the resources,” Kaplan said. “We’re nowhere close to investing what needs to be invested in what would truly shift things.”

The health department’s 2025 budget is $140 million less than its 2024 budget of $2.1 billion, with the difference mostly in the family and child health and disease prevention and treatment programs. The city’s hospital system’s 2024 budget was $174 million less than in 2023.

Much of the city’s public health spending comes from the federal government, and President Donald Trump has vowed deep cuts to health and other agencies.

Owen Racer is a freelance writer for Healthbeat, based in New York.