Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free New York City newsletter here.

With measles cases on the rise in the United States, public health experts in New York are encouraging vaccination against the highly contagious virus.

Measles spreads easily and can lead to serious complications, or death, among those who are unvaccinated. New York City has confirmed two cases of measles so far this year, according to Chantal Gomez, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Both cases involved unvaccinated infants, who have since recovered. The cases were unrelated.

In nearby New Jersey, three connected measles cases have been confirmed this year. A significant measles outbreak has also emerged on the Texas-New Mexico border, with more than 200 cases reported as of Friday. Last week, an unvaccinated child in Texas died from measles — the first known measles fatality in a decade — and on Thursday, officials announced the death of an unvaccinated adult with measles in New Mexico.

Dr. Jennifer Duchon, the pediatric hospital epidemiologist and director of antimicrobial stewardship at the Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital, emphasized that measles is preventable through vaccination.

“We don’t need to have measles outbreaks,” she said. “We have a preventative strategy. People don’t need to get sick, and children don’t need to die from this disease.”

Here’s what to know about measles and how to protect yourself and your family.

How contagious is measles?

Measles is far more transmissible than the flu or Covid-19. The virus remains active and contagious in the air or on infected surfaces for up to two hours, according to the World Health Organization.

That means that if someone with measles enters a room of unvaccinated people, everyone would likely become infected, said Dr. Mark Jit, chair and professor of the Department of Global and Environmental Health at the NYU School of Global Public Health.

In the 1950s, before the development of vaccine, nearly all children had measles by the age of 15, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of the three million to four million Americans infected each year, about 400 to 500 people died.

The measles vaccine became available in the 1960s, followed by the combination measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine in 1971. In subsequent decades, as vaccination coverage increased, measles cases fell.

In 2000, measles was declared eliminated in the United States. Today, most measles cases that emerge in the United States are imported through travel to countries with high rates of the disease.

What do we know about measles cases in New York City?

In addition to New York City’s two confirmed measles cases, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, reported a confirmed case of measles in an unvaccinated child who traveled by bus last week from John F. Kennedy International Airport in Queens to Philadelphia.

The Health Department is aware of that case, but New York City residents were not considered at risk, said Dr. Jennifer Rosen, the Health Department’s director of epidemiology and surveillance. She did not elaborate on how the agency made that determination.

Since New York City is a global travel hub, it’s not uncommon to see measles cases emerge through travel to other countries, she said. But outbreaks are rare.

“That’s really a testament to high vaccination coverage overall in New York City, and particularly among school-aged children,” she said.

Still, vaccination coverage is not equally distributed, and areas with low vaccination rates can increase the risk of local outbreaks.

That’s what happened in 2018, when an unvaccinated child returned to the city from a trip abroad, sparking a large outbreak among Orthodox Jewish communities in Brooklyn, with more than 600 cases by the following summer. The outbreak caused serious illness, particularly among unvaccinated children, but no deaths were reported.

For Rosen, that outbreak highlighted the importance of prompt vaccination and achieving herd immunity, which refers to the percentage of immunized people needed to ensure that a disease can’t spread widely in a community. For measles, herd immunity requires about 95% of the population to be vaccinated, according to the WHO.

“If most people in the community are protected, then even if one person gets measles, they can’t transmit it to anyone, because everyone around them is vaccinated,” Jit said.

How high are New York City vaccination rates?

Overall, MMR vaccination rates in New York City are very high. By kindergarten age, 98% of children have received two doses of the MMR vaccine, according to Health Department data.

But the rate of vaccination among younger children is lower, and has fallen in recent years. For children ages 24 to 36 months, the current coverage for one dose of the MMR vaccine is 81%, a decline from 88% in 2019, according to the Health Department.

The lower rate of vaccination for younger children indicates that “we have work to do,” Rosen said.

It’s a concern for the rest of the state as well. In a recent release, the state Health Department warned that current MMR vaccination rates among 2-year-olds have fallen below herd immunity levels in all counties outside of New York City. Only 81.2% of 2-year-olds statewide, excluding New York City, have received one dose of the MMR vaccine, and some counties have rates under 65%.

What are measles symptoms and how are they treated?

Measles symptoms typically appear a week or two after contact with the virus, and can include a high fever, cough, runny nose, red eyes, or a rash, according to the CDC.

Initially, symptoms can be quite general, making it hard for caregivers or health care providers to differentiate measles from other diseases, Duchon said.

But there are telltale signs. Children experiencing the initial stages of the disease are more “miserable” than they would be with a typical cold or cough, and often have a high fever, Duchon said. About three to five days after initial symptoms, a rash typically develops, which turns white when pressed. The rash tends to start in the face and spread across the body.

Not all measles symptoms look the same, and effects can vary as well, she added.

The disease can lead to encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain, which can be deadly. Measles can also weaken the immune system, making a patient vulnerable to secondary infections like pneumonia. A patient’s diminished immune system can persist for years.

There is no treatment for measles, Duchon said, and care for a patient tends to be supportive. On average, one to three in every 1,000 children infected with measles die.

How can you protect against measles?

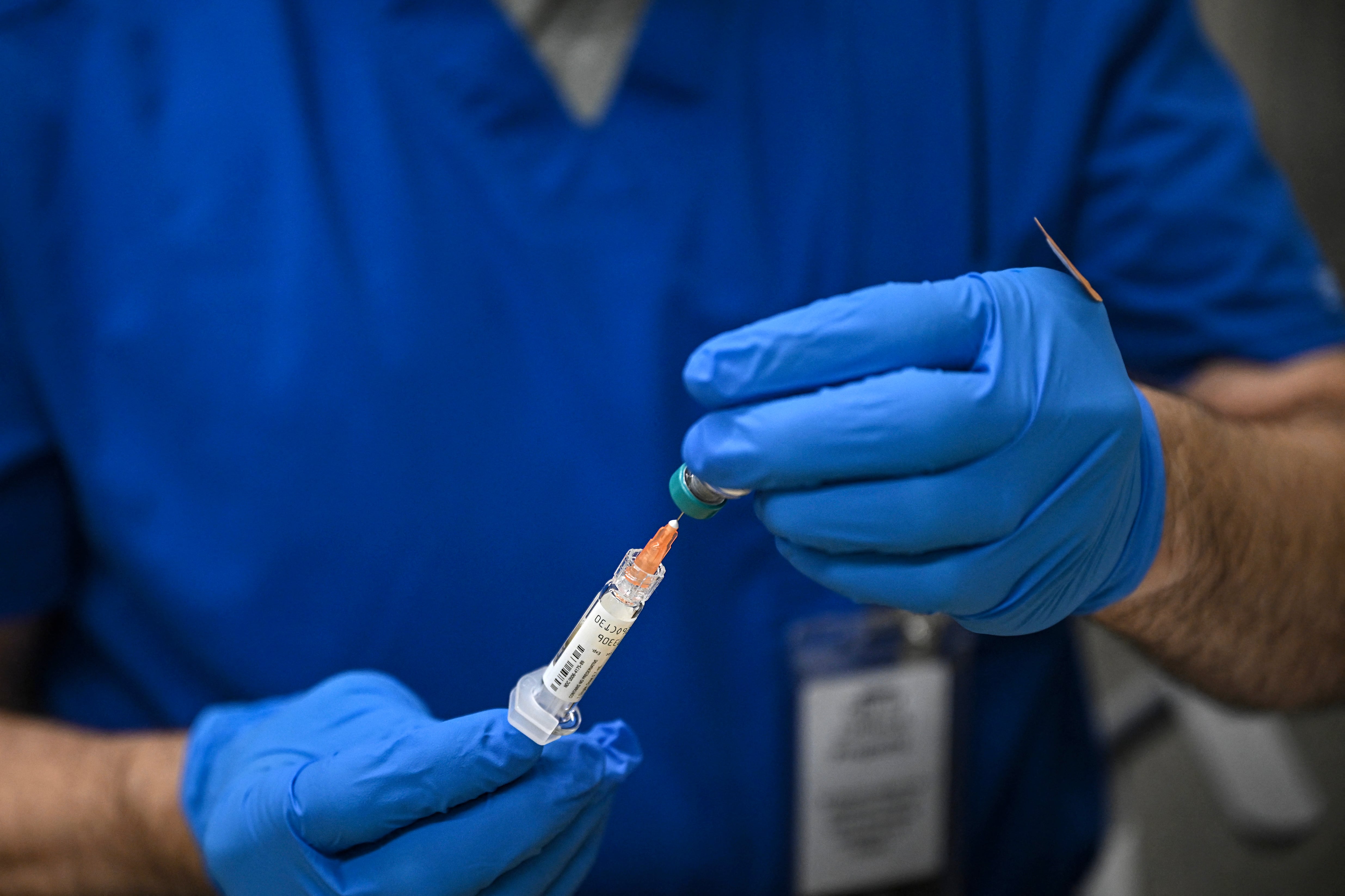

Vaccination is the best way to avoid becoming sick with measles, according to doctors and public health experts.

The CDC recommends that children get two doses of the MMR vaccine, with a first dose at 12 months old and a second dose at 4 to 6 years old. Two doses of the MMR vaccine are 97% effective at preventing measles. Most people vaccinated against measles are protected for life.

“The vaccine is safe and efficacious,” Duchon said.

In the late 1990s, a now-debunked study by a British researcher connected an increase in autism diagnoses to the MMR vaccine. Overwhelming scientific evidence shows that the vaccine is not associated with an increased risk of autism.

An early dose of the MMR vaccine is also recommended for children ages 6 to 11 months who are traveling internationally or in the case of a local outbreak. Those children will still need to receive the full two-dose course of the vaccine at 12 months and at 4 to 6 years old.

Eliza Fawcett is a reporter covering public health in New York City for Healthbeat. Contact Eliza at efawcett@healthbeat.org.