Sign up for Your Local Epidemiologist New York and get Dr. Marisa Donnelly’s community public health forecast in your inbox a day early.

A lot going on in the world of public health — here’s some news New Yorkers can use.

Bird flu confirmed on Long Island

Last week, dozens of dead ducks, geese, and seagulls infected with bird flu washed up on Long Island beaches.

Bird flu has now been detected in birds in 44 of New York’s 62 counties. No cases of humans or cattle in New York have been reported.

Why it matters:

Bird flu spreads easily among wild birds and poultry, disrupting ecosystems and farms and posing risk to those who work with animals. It’s also making our eggs very expensive.

It’s particularly deadly for birds, reaching close to a 100% fatality rate. In January, a Long Island farm outbreak led to 100,000 ducks being culled. (This is a biosecurity measure to mass-kill animals so it doesn’t continue spreading on the farm.) While human risk remains low, awareness and precautions are key.

What you should do:

- Do not touch dead or sick birds. If you see dead birds anywhere, assume they have bird flu. Several Americans outside of New York have been directly infected by sick birds. If you must dispose of dead birds, wear gloves, a N95 mask, and eye protection.

- Use a shovel or a garbage bag to pick up the bird, avoid direct contact with the carcass or carcass fluids.

- Report sightings of dead birds to the Department of Environmental Conservation using this form.

- If you have flu-like symptoms after exposure, call your doctor.

Fentanyl continues to drive the overdose epidemic in New York City

Last week, a 4-year-old child died from possibly ingesting fentanyl in a Brooklyn shelter.

This is a tragic reminder that fentanyl remains the leading cause of preventable overdose deaths in New York. In 2023, 2,444 New Yorkers died from a fentanyl-involved overdose — that’s one overdose death in NYC every four hours.

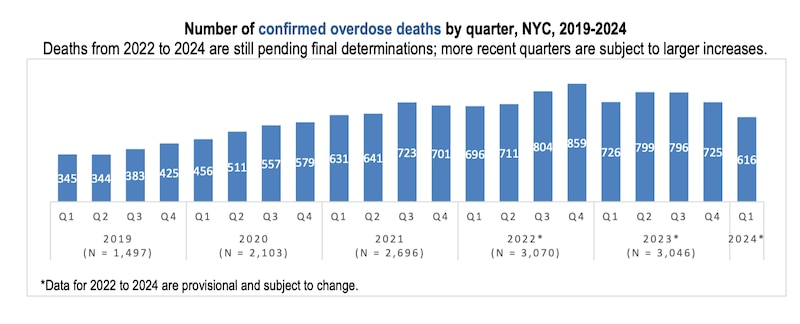

Though rates remain high, there are glimmers of hope. Our most recent data, from the first quarter of 2024 (overdose data is notoriously delayed), shows the fewest overdose deaths in New York City since 2020. This followed a downward trend that started in 2023.

The latest report, explained by Healthbeat, found 3,046 deaths in 2023 compared to 3,070 deaths in 2022, representing a 1% decrease. There were also fewer deaths in the first quarter of 2024 compared to the same time the previous year.

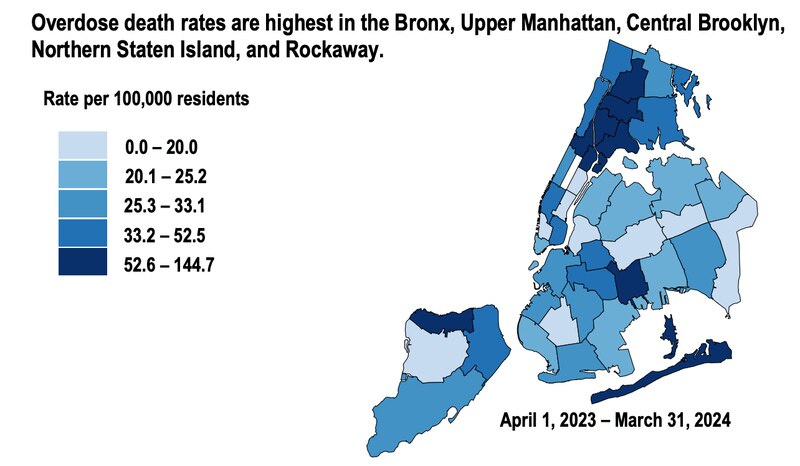

Overdoses remain particularly high in some New York communities hit hardest by the opioid crisis.

What you can do:

Carry Narcan (naloxone), a life-saving medication that reverses opioid overdoses.

- All New Yorkers can receive free naloxone and training from registered Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs (OOPPs) on how to recognize the signs of an overdose and administer naloxone.

- Health Department vending machines: Locations can be found on this page.

- Over-the-counter naloxone at pharmacies: Available without a prescription at most major chains (map here).

- Most insurance providers will cover all or part of the cost of naloxone, and New York State will cover copayments of up to $40.

There is also a hotline for individuals seeking support or treatment for substance use for themselves or their loved ones. Call or text 988, or visit the 988 website for 24/7, confidential support.

Mental health crisis care in New York: New proposals and their complexities

Involuntary treatment for mental illness is being actively debated in New York. Governor Kathy Hochul recently proposed expanding New York’s Mental Hygiene Law to help get people with mental illness access to treatment before they potentially become dangerous to themselves or others. Some advocacy groups say these changes undermine patients’ rights and could widen inequities in our mental health system.

This debate isn’t new. Every state allows short-term involuntary hospitalization for people experiencing severe mental health crisis, such as those at risk of suicide, often holding them for up to 72 hours to stabilize and arrange care.

The question New York is facing is where to draw the line between protecting individuals and preserving their autonomy while their mental state puts them or others at risk.

What would the proposals change?

The proposed updates focus on expanding intervention options and adjusting hospital procedures. Key provisions include:

- Broadened commitment criteria: The rationale is to allow earlier intervention for those unable to meet basic needs due to mental illness before self-harm or harm to others occurs.

- Hospital rules: Requiring hospitals to consider patients' long-term history and the frequency and outcomes of past crises — not just their current state — for involuntary admission or discharge decisions.

- Provider expansion: Authorizing psychiatric nurse practitioners, not just psychiatrists, to approve involuntary holds.

- Strengthened outpatient oversight: Simplifying the renewal process for court orders under Kendra’s Law, which mandates continued outpatient treatment, including taking medication, after discharge.

The debate and pushback

Supporters argue these changes could prevent crises and get people the care they need sooner. However, critics, including some committees and civil rights groups, have raised several concerns:

- Stripping individuals of freedom or bodily autonomy.

- Lack of investment in street-level mental health workers.

- Racial biases. Black and Hispanic populations have been disproportionately enrolled more than white people since the inception of Kendra’s Law.

- Lack of evidence. Critics say it’s unclear whether involuntary treatment is better than peer support or peer-led mental health crisis response teams.

According to a report by the New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, as of Feb. 25, 3,674 people were under an active involuntary outpatient commitment order statewide, including 1,684 in New York City.

Moving forward

New York’s mental health problem is deeply intertwined with housing instability, economic hardship, and racial disparities. While these proposals attempt to address real and urgent issues, there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Regardless of the outcome of these changes, there is a clear need to improve mental health services for our most vulnerable New Yorkers.

If you see someone in crisis:

- Don’t hesitate to seek assistance from a trained professional.

- If there is no imminent risk of danger, call or text 988.

- If someone appears to be an immediate danger to themselves or others, find a safe location and promptly call 911.

Bottom line

It may seem like the issues surrounding bird flu, the fentanyl overdose crisis, and mental health support have little in common. However, they are connected by our ability to take action to mitigate these concerns and improve community safety. We can contribute by reporting dead birds, carrying naloxone, or seeking help for someone in a mental health crisis.

Love,

Your Local Epidemiologist

Dr. Marisa Donnelly, a senior epidemiologist with wastewater monitoring company Biobot Analytics, has worked in applied public health for over a decade, specializing in infectious diseases and emerging public health threats. She holds a PhD in epidemiology and has led multiple outbreak investigations, including at the California Department of Public Health and as an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Marisa has conducted research in Peru, focusing on dengue and Zika viruses and the mosquitoes that spread them. She is Healthbeat’s contributing epidemiologist for New York in partnership with Your Local Epidemiologist, a Healthbeat supporter. She lives in New York City. Marisa can be reached at mdonnelly@healthbeat.org.