Sign up for Your Local Epidemiologist New York and get Dr. Marisa Donnelly’s community public health forecast in your inbox a day early.

As the leaves change, we say goodbye to summer, but at least one thing remains for a couple more weeks — mosquitoes.

Yes, mosquitoes are annoying, but they can also pose serious health risks for New Yorkers. It’s worth grabbing mosquito spray for a couple more weeks.

Here’s what’s going on with mosquitoes in New York (state and city) and especially the two diseases making the news.

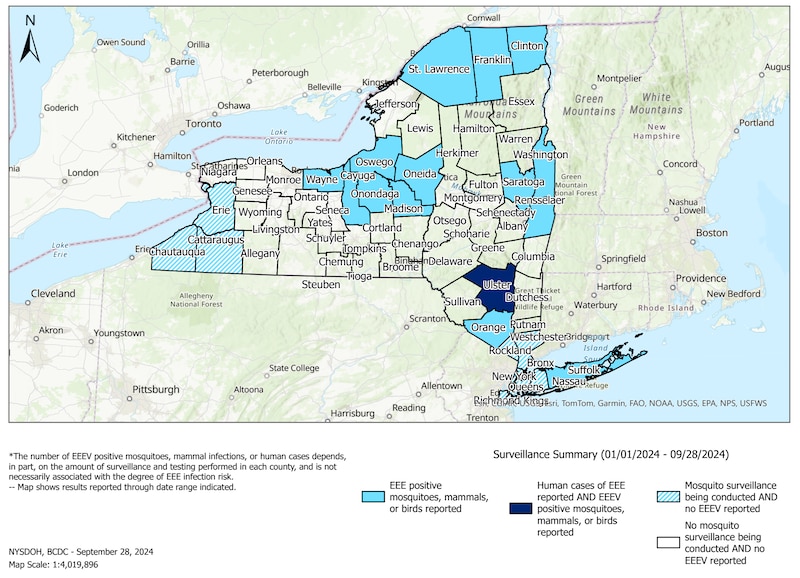

New York state reports human case of EEE

This is the first case in the state since 2015. The case was identified in Ulster County and the patient died.

Eastern Equine Encephalitis is a virus transmitted by the bite of a certain species of mosquito. Thankfully, most people infected with EEE won’t have any symptoms. But for those who develop symptoms, the illness can be severe and involve inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) and spinal cord (meningitis).

- About one-third of people who develop severe illness die.

- There is no specific treatment available.

- People over the age 50 or younger than 15 are at greatest risk.

EEE rare in New York, but may be more active this year

Since 1971, only 12 human cases have been identified in the state, including the most recent one. Of these patients, seven died. A human case of EEE is a significant event.

There are some signs that this year might be worse than recent years. Typically, two or three New York counties detect EEE annually by testing mosquitoes, horses, and birds. This year, though, 14 counties have detected it all across the state. And this isn’t because there is more testing this year; the level of testing is similar to last year.

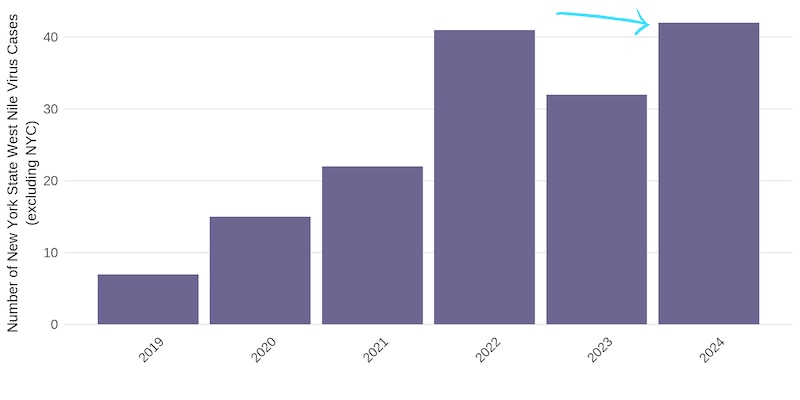

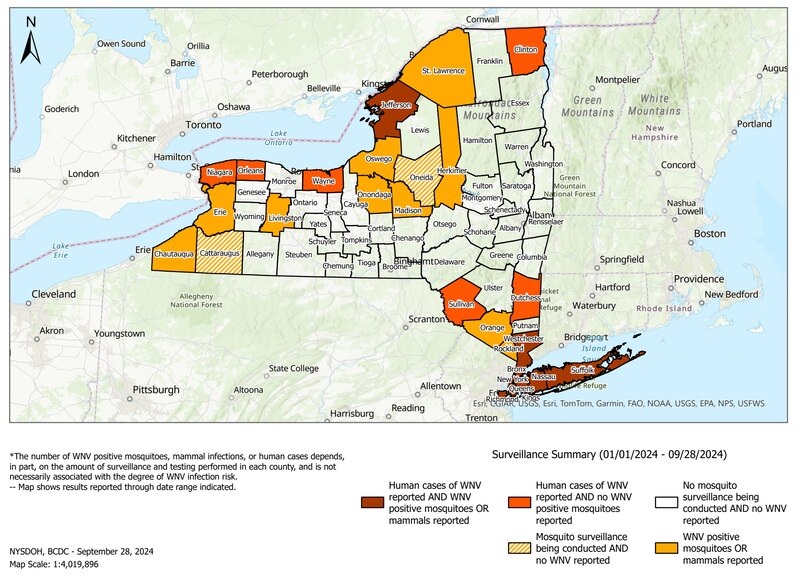

West Nile virus is circulating in New York City and state

West Nile virus is also a disease spread by some mosquitoes and is more common than EEE.

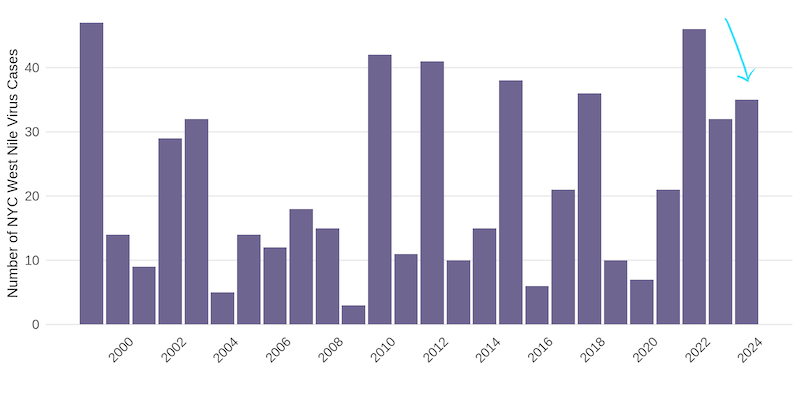

So far, 42 human cases have been detected in New York state (excluding New York City) and 35 cases in New York City. Compared to the past few years, this has been a normal year.

WNV has been detected in most of the New York counties that are testing for it. On the map below, solid light or dark orange and brown counties have had WNV detections in humans, mosquitoes, horses, or birds.

If we zoom in on New York City, we are also in the average range of WNV human cases. Over the past 10 years, the total number of annual cases has ranged from 6 to 46.

WNV-positive mosquitoes are almost everywhere in the city. Below, regions in blue are where West Nile virus has been detected in the past two weeks (light blue) and earlier this season (dark blue).

The number of WNV cases in the city is similar to the rest of the state (35 vs. 42) for two reasons:

- The high population density in the city — more people are there to get bitten.

- There is a lot of WNV activity. When adjusting for population size, Richmond (Staten Island) and Queens counties have some of the highest WNV case rates in the state.

Most people infected with WNV will not have symptoms or will have very mild illness. However, those over 60 years old or with immunocompromising conditions are at higher risk for severe illness, which can include inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) and spinal cord (meningitis), or muscle weakness or paralysis (acute flaccid paralysis).

What is being done to prevent more human cases?

A lot!

First, public health departments randomly test mosquitoes. Mosquitoes are collected in traps, identified in the lab, and tested in groups (for efficiency). We’ve been doing this for decades, and although imperfect, it gives us a good view of risk.

With consistent positives (in mosquitoes or humans), vector control units will then go to these areas and spray mosquito repellent in mass. Several factors go into the decision to spray:

- Mosquito density and species

- Persistence of the virus

- Time of year

- Proximity to human populations

While mosquito spraying is safe for humans and pets, if spraying is happening in your neighborhood and you have asthma or other respiratory conditions, it’s a good idea to try and stay inside during the spraying time.

There are no mosquito spraying events scheduled for New York City in the near future. You can check for schedule updates here. For spraying events in other areas of New York state, check with your local public health or mosquito control departments.

On top of ongoing mosquito control, New York state health commissioners issued a Declaration of Imminent Threat to Public Health in response to the Ulster County EEE case. This move:

- Frees up additional state resources to go toward reducing mosquito-borne diseases, including more public outreach and strengthening public health surveillance to detect human cases and positive mosquitoes

- Increases mosquito spraying throughout the state to reduce the adult mosquito population

- Provides free insect repellent to visitors at New York state parks and campgrounds

When will the mosquitoes leave?

Mosquitoes can only transmit these diseases when it’s warm. Once average temperatures drop to around 60°F, mosquito biology makes transmission much more difficult. It likely won’t be that cool consistently in New York until late October or early November, so until that happens, we should all be diligent about protecting ourselves from mosquitoes.

To avoid contracting WNV or EEE, the best thing you can do is avoid mosquito bites:

- Wear EPA approved mosquito repellent when outside and especially during peak-mosquito activity time: dawn and dusk.

- Avoid being outside when mosquitoes are most active (the morning and evening) — but this can be really hard.

- Dump standing water (think flower/plant saucers, buckets, fountains, toys that have been sitting outside, etc.) to eliminate mosquito habitats.

Bottom line

We are still in mosquito season. Because mosquitoes can carry some nasty diseases, keep that mosquito spray close for a few more weeks!.

Love,

Your Local Epidemiologist

Dr. Marisa Donnelly, a senior epidemiologist with wastewater monitoring company Biobot Analytics, has worked in applied public health for over a decade, specializing in infectious diseases and emerging public health threats. She holds a PhD in epidemiology and has led multiple outbreak investigations, including at the California Department of Public Health and as an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Marisa has conducted research in Peru, focusing on dengue and Zika viruses and the mosquitoes that spread them. She is Healthbeat’s contributing epidemiologist for New York in partnership with Your Local Epidemiologist, a Healthbeat supporter. She lives in New York City. Marisa can be reached at mdonnelly@healthbeat.org.