Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

At a health expo in Clarkston, workers offering services expressed pride in their efforts to contribute to metro Atlanta’s well-being. But many worried whether moves by newly elected President Donald Trump could hamper their mission.

Organizations filled a Georgia State University Perimeter College atrium Wednesday with booths offering health services to students and the broader community.

At one booth, Will Settle stood behind a table draped in a cloth with the logo for SisterLove, an Atlanta nonprofit focused on improving women’s reproductive health access.

Settle, a consultant for the agency, offered passersby information about sexually transmitted diseases and directed those interested to the organization’s mobile testing bus parked nearby. He’s proud of SisterLove’s efforts to share information about sexual health and finding ways to connect low-cost HIV preventive medication to people who need it.

“If you have HIV, it is no longer a death sentence,” he said. “A lot of people don’t know that this is something that is available.”

Cuts could impact local HIV, reproductive health initiatives

This week has been filled with uncertainty for people like Settle and organizations like SisterLove. On Monday, a memorandum from the Office of Management and Budget directed federal agencies to stop distributing most of their funds. The letter cited Trump’s desire “to increase the impact of every federal taxpayer dollar” as a reason to halt the spending.

The directive was stalled and withdrawn before it could take effect, but Trump has vowed to still make drastic cuts that could affect how organizations like SisterLove operate. To connect people to low-cost HIV prevention medications, the nonprofit relies on a federal program that makes life-saving drugs more affordable — a program that may have been affected by the Budget Office’s order.

“We’re trying to get as much information, just like everyone else, as we can,” Settle said. “So it’s a wait and see.”

Settle said a funding stoppage, in addition to a flurry of executive actions Trump has been signing over the past two weeks, could have profound effects on Atlantans’ health. While he said SisterLove receives more of its operating budget from private partners than from the federal government, cuts that affect those partners could jeopardize the organization.

The threat comes at a critical time for Atlanta, Settle said, as nonprofits have been helping to address the city’s health care gaps left by recent hospital closures.

“If we’re impacted, that’s going to impact the folks in our community,” he said. “They’re not going to be able to get the access to health care that they desperately need.”

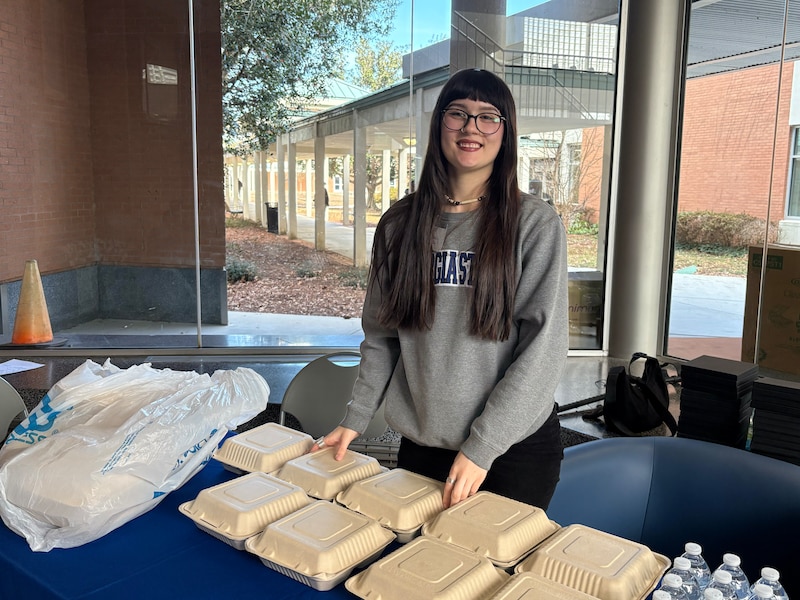

Future public health efforts were also on the minds of Makayla Jackson and Kayla Osmon, two second-year master of public health students who were working at the expo. They are interns with GSU’s Prevention Research Center, a program funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Jackson, who helped check in attendees, was excited for the opportunity to connect fellow students with free health services like SisterLove’s testing. She wants to continue advocating for health equity after she graduates later this year, although she knows that could be hard if some of Trump’s initial priorities are carried through in policy.

If there’s little money available to do that work, she said she would consider doing volunteer health equity work instead. But she hopes it doesn’t come to that.

“It is frustrating,” Jackson said. “I could always find employment, but my life is not threatened. So I’m more concerned about other vulnerable populations.”

Concern for underserved communities in metro Atlanta

Osmon also expressed concern about the health of underserved communities in the metro Atlanta area. Much of the Prevention Research Center’s work focuses on the mental health of Clarkston’s refugee, immigrant, and migrant residents, who often experience unique challenges accessing this type of care.

Over the past month, Osmon said she’s seen the stress of Trump’s immigrant-targeted executive orders take a mental toll on the groups she’s working with.

“We’re kind of in this stage of not really knowing how things are going to go, and how people are going to be treated, and how people’s lives are going to be affected,” she said.

Osmon said she took inspiration from the other health professionals around the expo — like the group set up across the atrium that was working a booth for ICNA Relief, a national health care and social services nonprofit with offices in the Atlanta area.

One man at the table, Dr. Dawood Rateb, quickly offered blood pressure tests and glucose level screenings to anyone who walked by. Until a few years ago, Rateb and his wife practiced as doctors in Afghanistan. But he said his work as a medical interpreter for the U.S. military opened his family up to Taliban retaliation, making it dangerous for them to remain in the country.

Two years ago, Rateb and his family found refuge in the Atlanta area through the Department of State’s Refugee Admission Program, which Trump has ordered to stop taking new arrivals until “the further entry into the United States of refugees aligns with the interests of the United States.” Now, he and his wife both work as health coordinators for ICNA.

While the future may be uncertain, Rateb said that for the time being, he and his wife were happy they could offer their time and skills to help the Clarkston community be healthy.

“Today we are here, and we are so excited.”

Allen Siegler is a reporter covering public health in Atlanta for Healthbeat. Contact Allen at asiegler@healthbeat.org.