Sign up for Your Local Epidemiologist New York and get Dr. Marisa Donnelly’s community public health forecast in your inbox a day early.

Have questions, comments, or ideas for future topics? Email me at mdonnelly@healthbeat.org. I would love to hear from you.

After navigating to the New York respiratory virus dashboards, where I usually start my analysis for these reports, I breathed a sigh of relief. The data were still being updated, and I could do my job: translating public health science for you.

Before we get into the state of affairs of respiratory illnesses, though, here is what is happening with data at the federal level and why New York has been spared the widespread closures of federal data sets we’ve seen this week.

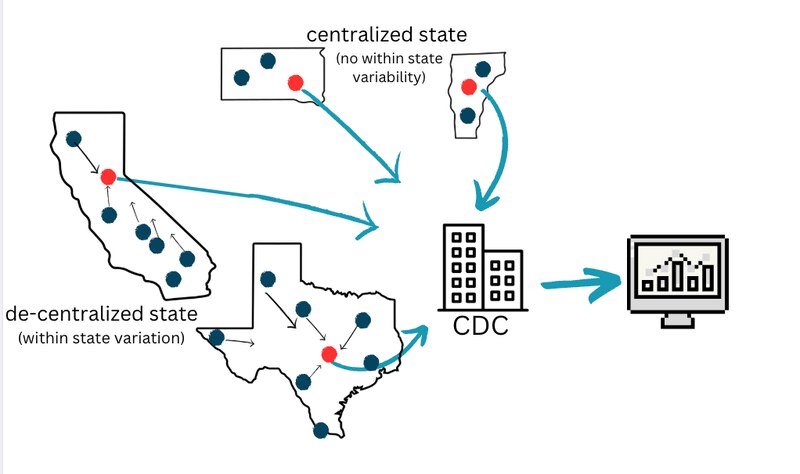

Decentralized public health system

In the United States, our public health system is decentralized. This means that local and state health departments collect and own the data rather than the federal government. During the Covid-19 pandemic, limitations to this setup slowed our understanding of what was happening nationally — the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had to knit all the local and state pieces together. However, with current uncertainties surrounding federal data sharing, this is a good thing, as it provides a sort of firewall.

All states have slightly different models of how this works.

New York is a mostly decentralized state. Local health departments retain authority and are led by local government employees. They collect health data from their communities and share it with the state and then with the CDC. Data flow from the bottom up, and remain available to us regardless of what the feds do or don’t do with it. Importantly, states don’t have to send the majority of data to the CDC (really only hospitalizations).

While this is good news, there are some vulnerabilities associated with a potentially weakened CDC that epidemiologists like myself are paying close attention to:

- During big outbreaks or public health emergencies, like a measles outbreak or hurricane, coordination across states and with the CDC is absolutely essential. We often rely on CDC expertise when new or rare diseases pop up.

- Reduced funding for the CDC would affect local and state health department funding. Eighty percent of local and state public health funding comes from the CDC.

- Not all states have the resources to maintain their own health dashboards, like in North Dakota, for example. Many rely on CDC’s dashboards, and without them, residents of those states could be left without critical public health information.

What this means to you and New York communities

New York can (and continues to) publish its data for New Yorkers without interference from federal government chaos. For example, dashboards for influenza, RSV, Covid-19, and wastewater remain unaffected.

With gratitude for the strength of our New York public health system, let’s dive into the most recent data on respiratory viruses.

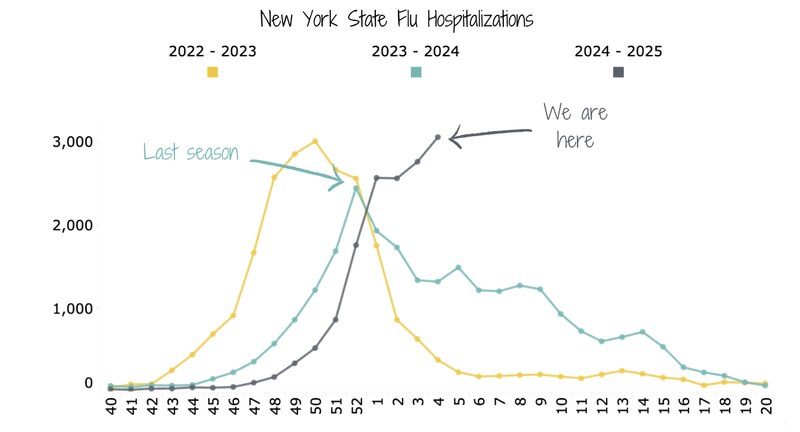

The flu: High and increasing

The number of people with flu in New York is abnormally high for this time of year, and the increase is widespread across all state regions. With so much flu, New York hospitals are being pushed to their limits. In Rochester, for example, recent spikes in flu hospitalizations have pushed the Strong Memorial Hospital beyond its capacity.

New York’s flu season started later than last year’s, but it’s shaping up to be worse. Severe flu infections requiring hospitalization are the highest they’re been in three years and may not have peaked yet. Over the past two seasons, flu hospitalizations peaked before New Year’s Day.

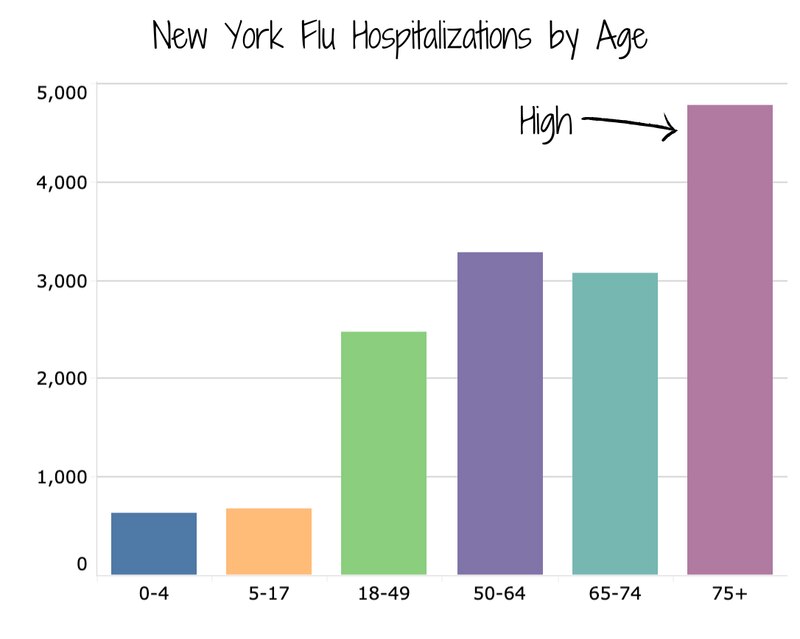

We’re seeing the flu hit nursing homes and older populations hard. In the week ending Jan. 25, 41 outbreaks were reported in nursing homes — a 32% increase compared with the previous week. This is concerning because older residents are at much higher risk for bad flu outcomes: In a typical season, about 70-85% of flu deaths are among people age 65 or older (CDC Flu). Across the state, flu hospitalizations are highest in the 75+ age group.

With the flu so high, there are a couple of things we can do to protect our most vulnerable fellow New Yorkers, including:

- Wearing a mask in crowded spaces (while traveling, on the subway, in supermarkets, etc.).

- Avoiding social interactions if you aren’t feeling well.

- Getting vaccinated.

- Flu usually has a second peak later in winter due to flu B circulation (right now, most flu cases are from flu A), and infections can go into March or April, so it’s not too late to get your flu vaccine at a local pharmacy or clinic.

- People who are at increased risk of serious flu complications (pregnant people, people over age 65, people with asthma and chronic lung disease, diabetes, or heart disease) should contact their doctor for possible treatment within two days of symptom onset.

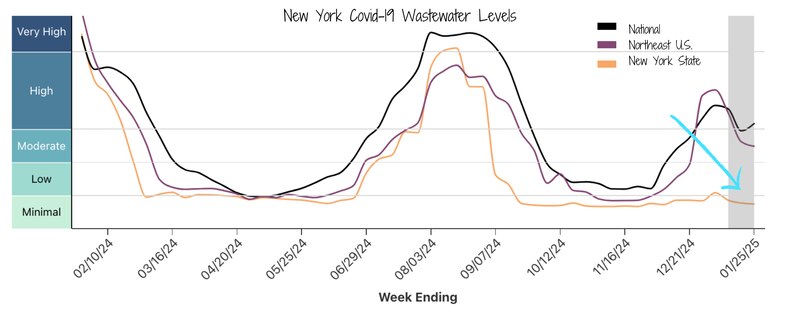

Covid-19: Minimal and holding steady

Covid-19 activity in New York has remained surprisingly low — this is our mildest Covid-19 winter to date.

It’s striking that Covid-19 levels are so low in New York compared to national and Northeast regional averages. High community immunity from vaccinations and past infections — especially following a big summer wave — likely plays a role, but I don’t think it tells the whole story. Milder infections may be leading to less viral shedding, and behavioral changes like isolating when sick or masking could also be reducing spread. Given the high flu activity in New York, I also wonder if interactions or competition between respiratory viruses are slowing Covid-19 transmission.

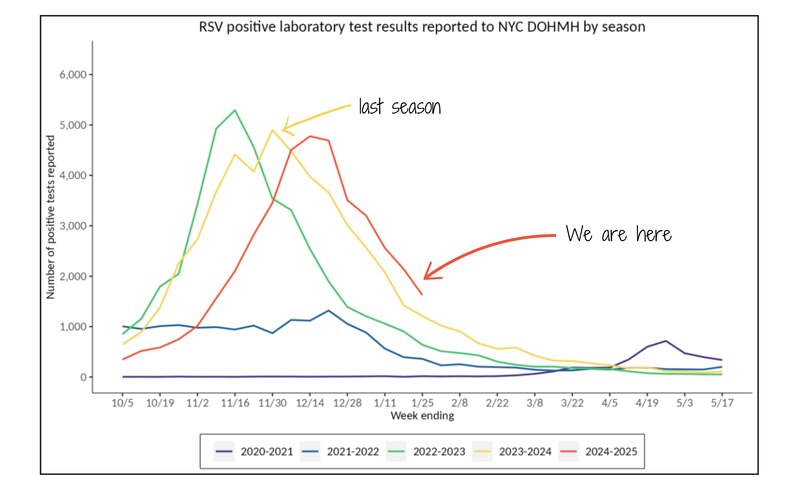

RSV: Moderate and decreasing

RSV has peaked and continues to decline in New York. This season looks like a middle-of-the-road RSV season, like last year’s. The shape of the RSV seasonal curve in New York is similar to the past three years.

We still expect there to be several weeks of RSV activity, so we aren’t entirely out of the woods yet.

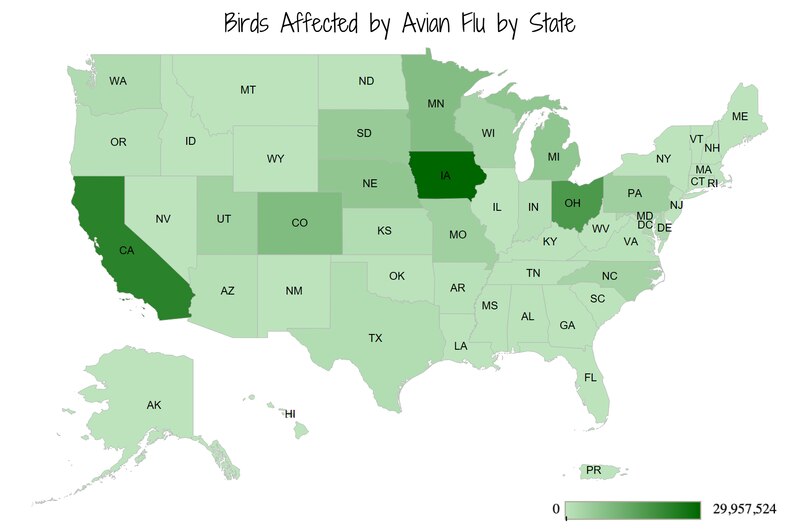

Emerging diseases: Avian flu

Two weeks ago, avian flu (bird flu, H5N1) was detected on a Long Island duck farm. This is important because, up to now, New York has been relatively spared the impacts of H5N1 compared to other states. We’ve had no reported cases among humans or cattle. The duck farm outbreak is only our second in a commercial flock statewide and our first in three years (United States Department of Agriculture Avian Influenza Tracker). Thankfully, New York agriculture and public health authorities are taking steps to prevent further spread.

All 100,000 ducks at the Crescent Duck Farm in Aquebogue on Long Island had to be culled (euthanized). Culling birds after an avian flu detection happens for two main reasons:

- To contain the spread by preventing transmission to other birds or animals, including humans. The goal is to keep this an isolated event.

- To protect public health by reducing opportunities for mutation. Every infection is a chance for the virus to pick up mutations that could make it more transmissible to humans and potentially spark a pandemic.

These efforts don’t come without risks. The workers tasked with culling animals are at high risk for exposure to the virus. Of the human avian influenza infections in the United States, 23 of 67 had exposure at poultry farms. Proper personal protective equipment and handling of animals are essential.

The risk of avian flu to the general public remains low, with no human cases reported in New York. But there are some precautions we can take, especially for those who spend time around birds or keep backyard flocks. In the past three years, 27 backyard flocks have tested positive for avian flu in New York.

- Report sick or dead birds immediately.

- For poultry, call the New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets at 518-457-3502.

- For wild birds, call the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation at 718-482-4922 or 518-478-2203.

- For other animal-related concerns, call 311.

- Avoid contact with birds that appear sick or have died, and avoid contact with surfaces that have bird feces.

- If you must touch sick or dead birds:

- Wear gloves and a facemask (preferably N95 or better).

- Place dead birds in a double-bagged garbage bag.

- Throw away your gloves and facemask after use.

- Wash your hands well with soap and warm water.

Avian flu has also been affecting cattle nationally. Thankfully, New York, which ranks fifth in dairy-producing states, has not detected avian flu in cattle. To bolster public health surveillance, New York joined a national USDA program to test bulk raw milk (both milk that will be pasteurized and remain raw) for avian flu. We are still being onboarded, and milk testing has not yet started.

Bottom line

These are uncertain times for federal public health agencies. I’m grateful we can rely on strong local and state public health systems in New York to keep us informed. For now, winter virus transmission, especially the flu, is still high. Stay healthy: Mask up, avoid social interactions when you’re sick, and get vaccinated.

Love,

Your Local Epidemiologist

Dr. Marisa Donnelly, a senior epidemiologist with wastewater monitoring company Biobot Analytics, has worked in applied public health for over a decade, specializing in infectious diseases and emerging public health threats. She holds a PhD in epidemiology and has led multiple outbreak investigations, including at the California Department of Public Health and as an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Marisa has conducted research in Peru, focusing on dengue and Zika viruses and the mosquitoes that spread them. She is Healthbeat’s contributing epidemiologist for New York in partnership with Your Local Epidemiologist, a Healthbeat supporter. She lives in New York City. Marisa can be reached at mdonnelly@healthbeat.org.